A different idea of teaching: Self-awareness in the classroom

Grazia Perigozzo

Wednesday, September 1, 2021

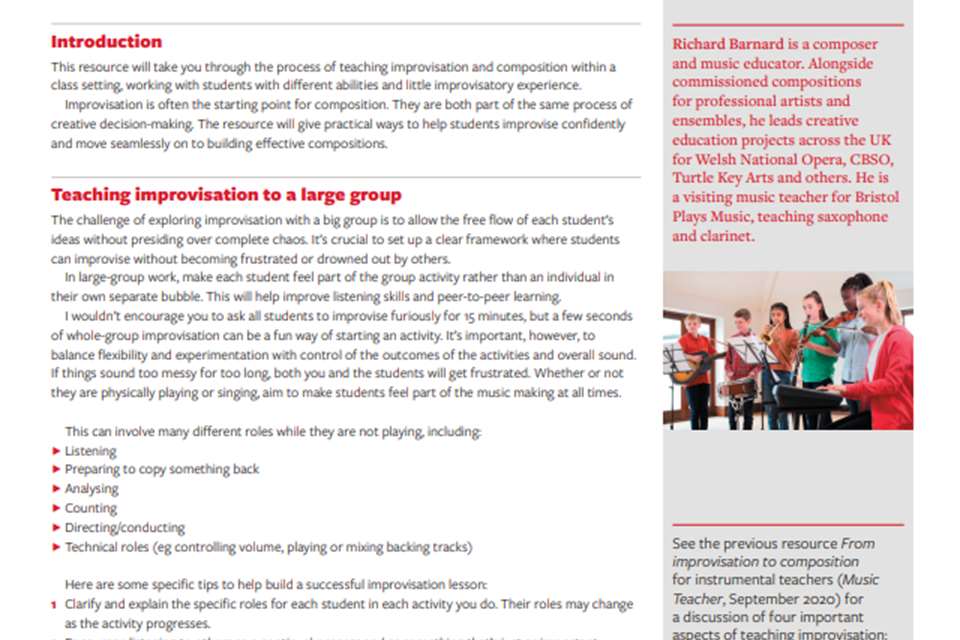

As teachers, do we sometimes need to let go of our own agendas to prioritise students' creative freedom? Pianist, educator, and researcher Grazia Perigozzo shares her journey of self-awareness in the music classroom.

To think of a school is naturally to conjure up certain associations: knowledge, skills, training, and so on. When we remember our own experience of schooling, though, our memories often hinge instead on more transient moments of success and failure, sadness, and joy – in short, the sum of the emotional world which we inhabited.

Whatever specific subjects or disciplines we learn, we also ‘learn’ feelings, and moreover – if we are lucky to meet the right teacher(s) – how to manage them. For most this is a truism, but what is less obvious is that this confrontation with feelings is directly connected to the development of our unique sense of freedom. I try here, with reference to my own experience and research in music education, to elucidate this point and some salient pedagogical issues which arise from it.

What are we working towards?

A student's experience, especially in creative disciplines like music, progresses as a reflection of the way in which they are perceived and treated by their teacher. Students who believe themselves regarded as ‘ordinary’ will manifest precisely that behaviour: the need for challenge and the desire to test new waters can quite easily turn to indifference and even fear. On the other hand, students can develop skills with mysterious speed, tapping into hitherto unsuspected resources of capability, when they see themselves to be genuinely and individually appreciated. We refer to this as the growth of self-image. Nothing I have said so far, I hope, is controversial.

And yet there often exists within this paradigm a certain trap. Whether consciously or unconsciously, a set of mutual expectations between student and teacher can begin to form; the sense of positive reinforcement leads the student to respect above all the predetermined path which the teacher has mapped out for them. They feel that embracing another path would be risky, dangerous. This undoubtedly impacts on the sense of freedom so vital to a learner's creative evolution.

A question therefore took shape in my mind: are we teachers deeply aware that our teaching brings with it a cloud of emotions, ones which we must highlight? Are we simply offering a model to follow with the promise of ‘success', or are we truly working towards the expansion of our students' freedom?

Breaking the chains

I have long been intrigued by the formation of relationships in a classroom. Students may unconsciously arrange themselves into certain typologies – the teacher's pet, the class clown, the shy kid in the corner – simply in order to be ‘accepted’. Certainly, these models of identity are fluid, especially during adolescence. Nonetheless, they are often reinforced by the teacher. An attentive teacher, of course, seeks to reinforce positive models, but even these, it seems to me, can have a limiting or constrictive impact on personality development. The question, then, becomes: how do we break the chains which these models engender?

My principal area of music education has always been chamber music. When each year commenced, I gave initial tests to gain a sense of my students' natural abilities and devised a scheme of work based on this. There were natural drummers, natural singers, natural instrumentalists. Soon after, each student would be assigned a role in their activities as chamber music learners; overwhelmingly, they accepted the roles I had decided, even grew fond of them. The roles became part of their comfort zone because they were what I, the teacher, expected. The results were always encouraging, and I convinced myself that my teaching method was right and appropriate.

Over the years, though, doubts began to creep in. My students followed me trustfully, perhaps eschewing their own reservations or their felt need to express themselves in some other way. I became aware that I was ‘directing’ more than guiding them, allowing them few creative choices of their own. Hesitantly, then, I started to leave my students free to decide their roles in chamber music, setting aside what I defined as my ‘expertise’. From this point, my lessons took a noticeably different direction.

Image: Grazia Perigozzo

Fear of failure

One year, teaching at a state secondary, a student told me unambiguously: ‘I want to sing.’ Four little words of profound significance. She just wanted to sing (how to say no?) and did so, totally out of tune. Others followed her lead and asked to do the same. By lunch, I found myself with a vocal section filled with students entirely out of tune.

In such a fashion my lessons began. At first, I was rigid, driven forward not by my students' own self-determined passion but by the fear that I would not achieve ‘results' as I had traditionally defined them. I saw that first student struggling to reach a passable intonation, and in this I saw clearly represented the gap between my students' natural abilities and skills on the one hand, and their desires and projections on the other. The question of priorities then arose. What is more important, I thought, the expressive freedom of my students, or the tangible musical outcome? And, what's more, how might these two priorities be married, such that one does not preclude the other?

Over the course of that year, I taught with perseverance. But until I came to look at myself honestly, few results were forthcoming. It was only when I did finally come to apprehend my own fear of failure, of seeing my hard work reduced to something amateurish and clumsy, of losing the pride in my success on which I depended, that things began to change. For dependence is precisely the antithesis of freedom. I determined to leave this sense of pride and the weight of expectation this involves behind me.

An epiphany

This snap of awareness marked the end of a long transformational process within me. In the classroom I found myself ever curious to discover new directions, embracing the reality of the moment without heed for past or future. The wrong notes and the poor intonation were still there, as they had been over the preceding months, but my worries seemed to have dissolved. I began to observe what I couldn't see before: what my students were giving to me, their own emotional involvements, their own will to succeed at what had been their own choice.

Day by day, that first girl who had told me ‘I want to sing’ began to lose her stiffness, which had in fact been the mirror reflection of my own rigidity. Her approach to singing changed, opening up a range of possibilities, unencumbered by the weight of my judgements and expectations. A sense of pleasure began to beam from her face, replacing what had been her gaze of cold determination, as she pursued her own role and her own choice.

Finally, she was singing with confidence and, almost always, in tune. She learned, along with her classmates, that commitment and expressiveness could emerge not simply from what she was naturally good at but from what she naturally enjoyed. This was her step towards real freedom, the kind towards which we gravitate but is too often buried by the ‘rules', ‘common sense’ and all the other mechanisms which we teachers, even involuntarily, pass on ourselves.

The end-of-year concert was more successful than it had ever been. A newfound passion among my students was evident in every page of sheet music. This new experience, for me, finally opened the door to a different idea of teaching. For them, it provided proof that it was possible to realise a dream.

My students and I learned to explore the unknown, living both the risks and the freedom this entailed, together.