Adapt and overcome: Take it away Consortium

Harriet Clifford

Sunday, August 1, 2021

Is music education truly inclusive if a disabled child or young person can't access the same opportunities as their peers? Harriet Clifford speaks to Creative United CEO Mary-Alice Stack about the Take it away Consortium and their work in mainstream primary schools.

NOYO/Clarion

Most people in the UK today would agree that the Paralympics is a ‘mainstream’ event. Many of us could name a few athletes, and hopefully all of us can at least recall a time when we've seen a Paralympian on television, in the media, or on an advert. This public recognition for disabled athletes has only emerged onto the global stage in the last 30–40 years – the Paralympics was first held in 1960 but wasn't twinned with the Olympic Games until 1988. ‘Disabled sportspeople are very present now,’ says Creative United CEO Mary-Alice Stack over Zoom. ‘In music, we're not there yet. But there is an opportunity for us to be at that level.’ The process of reaching that level, Stack makes clear, is still in its infancy.

Humbled beginnings

Back in 2018, Stack was working on the Take it away scheme, which had begun life 10 years earlier with support from Arts Council England and was originally dedicated to removing financial barriers to music learning and participation. The scheme had enabled the purchase of 90,000 instruments – the equivalent of over £60m worth of sales. Evidently an achievement to be celebrated, the team was gearing up to mark the scheme's 10th anniversary when Stack met with Rachel Wolffsohn, general manager of the OHMI Trust (One-Handed Musical Instrument Trust). ‘I had a real penny-drop moment meeting her, because it had just never occurred to me that in all the years we had spent trying to remove the financial barriers to owning musical instruments, it might be the instruments themselves that present an even greater barrier,’ says Stack. According to Department for Education (DfE) statistics, 31,459 children with a physical disability as their primary need attended a mainstream school in England in 2019.

Her ‘way in’ to this vast but often untapped area of the musical instrument market was clearly a humbling experience, and is likely reflective of the way in which many of us go through life ‘blissfully’ unaware of the accessibility issues thousands of people face each day. Stack decided that she couldn't unlearn or ignore what she had been told: ‘It opened my eyes to a whole new set of issues, which I felt were incredibly important for Creative United to consider as we looked forward to the next 10 years of the scheme. I wanted to make sure we were thinking very particularly about the music experiences of disabled people, either within or outside of education, and what we could do as an influencing body – all about access and inclusion – in the sector to help change that experience for the good, in partnership with others.’

This task required Stack and her team to start almost from square one, as despite the impressive numbers, Creative United had no data on the customers who may have had a physical disability. The company also had no direct experience of working within the disability space, so, as Stack explains, ‘It was essential for us to work with people and organisations with existing expertise in this area, to learn from them and understand all of the excellent work that had already been achieved. We didn't want to reinvent the wheel – we wanted to be able to draw those things together and use our position and relationship within the music retail sector to influence and advocate for change. A lot of progress has been made on access and inclusion in educational settings and within specialist organisations. But what were the levels of understanding in mainstream retail?’

Adaptive instruments

Fast-forward to today, and a consortium of specialist and non-specialist organisations are working together towards six agreed aims – Creative United and Take it away have partnered with the OHMI Trust, Drake Music, Music for Youth, Open Up Music, TiME (Technology in Music Education UK), and Youth Music to form the Take it away Consortium. Stack says their modus operandi is ‘very open and very flexible’, but everything they do as a group is focused around the six objectives (available online), which range from ‘Improve our collective understanding of the potential demand for adapted and specialist musical instruments’ to ‘Raise the profile of music making by disabled children and adults’. Last year, the consortium produced the Guide to Buying Adaptive Musical Instruments, which, in a concise document, lays out the different options available in conducting batons, brass, music technology, percussion, strings, and wind. These options include lightweight instruments, one-handed instruments, apps, supports and accessories for standard instruments, electronic instruments, and software.

Creative United and the OHMI Trust have been working closely together for the last three years on identifying and responding to the needs of physically disabled children in mainstream education, focusing specifically on the provision of adapted instruments in whole class ensemble teaching (WCET). ‘We had a particular objective which surfaced through the research that the consortium originally commissioned – the Make Some Noise research – which was subsequently published by Youth Music as the Reshape Music report,’ says Stack. ‘The impetus here was that when we tried to find out about the experience of disabled children in mainstream education, there was just no data.’ Their solution was to partner with Nottingham Music Service (NMS) and focus on one catchment area, in the hope that data collected can then be used to help make assumptions about areas elsewhere in the country.

‘We were able to establish very early on that, far from there being no children, there were many children who had a physical disability or an educational need that wasn't being fully understood or responded to, because nobody knew it was there,’ says Stack. She describes her frustration over the lack of information available to teachers, and therefore the fear many feel about being told that there is no solution, which often paralyses people. ‘I'm not saying it's easy, but it is impossible if you don't ask the right question at the right time,’ Stack adds. ‘If we find a solution, it means the child or children can have a much better quality of experience, alongside their peers, without being differentiated, without being told, “you can't play the guitar, you have to play something else” – because that's not what WCET is about.’

The project with NMS is ongoing and has already been expanded to include schools working with Northamptonshire Music & Performing Arts Trust. The aim is to eventually scale up the initiative, having demonstrated demand, and create a supply-chain of adaptive instruments through Music Education Hubs nationally. Despite the enormous complexities of the task, Stack says, ‘It's so wonderful when you get it right. Suddenly that child is given the opportunity to play the instrument they want and they're able to understand that they do have the ability to progress. If we really want to see the music sector become more diverse in terms of disability, we have got to give people a chance early doors.’

A human right

For teachers on the ground thinking about logistics, budgets, senior leadership teams and so on, reaching this point may seem not only complex, but impossible. Highlighting the necessity of systemic change, Stack says, ‘The law states that if you are disabled, society needs to make reasonable accommodations to allow you to participate to have quality of experience. This isn't a “nice to have”, it's a human right.’ She adds: ‘To say that that's problematic or expensive isn't really the appropriate response these days. It's got be a proactive, enabled response that makes teachers, parents and children feel like that's something they can and should do, not something that's being put to one side because it's complicated.’

One question may be: ‘How can I teach a child to play an adapted instrument if I don't know how to play it myself?’ Stack agrees that this is a valid concern and explains that the OHMI Trust is working with Birmingham City University to look at CPD training to help music teachers build that knowledge into their learning pathway. She adds: ‘It isn't a straightforward answer because it may be that the adaptation isn't a completely different instrument, but the solutions come in many different shapes and sizes as well. There is help, but people need to be confident to ask to be supported in acquiring that specialist knowledge.’

Looking to the future, Stack hopes that the Consortium will be able to create a centralised online hub for information to be shared and questions to be asked. In terms of getting music to the Paralympic level, Stack says that it might take us another 20 years. ‘But that's okay, as long as there are people who are campaigning for disabled people's rights in music education, performance, progression, celebration, and recognition. It won't happen if nobody flies that flag and says, “there are some incredibly talented musicians out there – let's see and hear them in all their diversity”.’

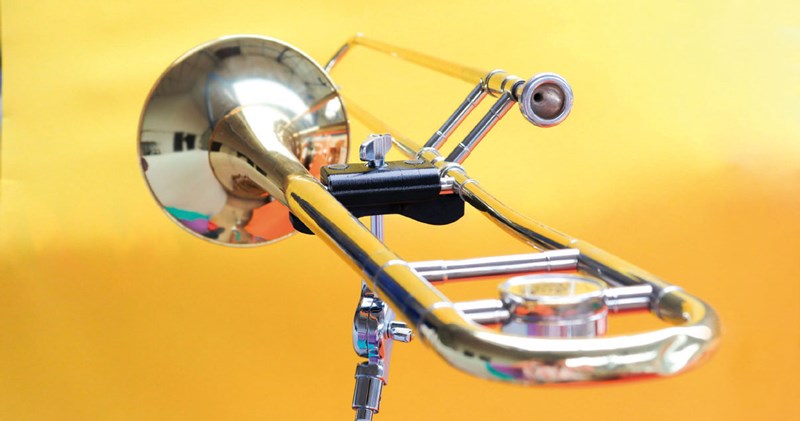

MERU Trombone Stand © Courtesy MERU

takeitaway.org.uk/news/adaptive-musical-instrument-guide

youthmusic.org.uk/reshape-music

Creative United is keen to hear from interested music teachers.