Deep dives – let's not muddy the waters

Jimmy Rotheram

Sunday, August 1, 2021

How do you demonstrate progression in music up to KS3? What should you be doing to prepare for an Ofsted deep dive? Jimmy Rotheram has some ideas.

micromonkey/adobestock

I am very tempted just to write an extremely short, four-word article about assessment here, which simply advises you to regularly film your classes doing music, taking a lead from the US Navy's ‘KISS’ philosophy of design: ‘Keep It Simple, Soldier!’. Alas, MT insisted on more words, but paying attention to musical outcomes and filming them regularly is the most effective method of tracking a student's progress over time. In a world of heavy number-crunching, assessment can easily turn into a broken, out-of-control Heath Robinson machine – convoluted, over-complex and thoroughly inefficient.

What's the point?

Assessment should always add value – identifying which pupils are struggling with which aspects, which teaching strategies have been successful and what has worked not-so well, so that it can inform our practice. Simple. But is it?

Teachers of a certain vintage can still remember the dark old days when every child had to be given a National Curriculum level – a tick list which was constantly monitored. We occasionally wake up in cold sweats at 2am, worrying about how we can get Year 8 up by three levels in two weeks to meet our targets. How do you give an overall level to a phenomenal drummer who can't sing in tune? Or a producer who can make machines dance, sing and cry, but who can't read a jot of notation? Video evidence would capture all of this in a way that numbers, levelling, books, and constant comparison with other children simply couldn't. It can also create unhealthy comparisons between pupils and their peers. I'm with Bartok on this one: ‘Competition is for horses, not artists’ – especially with younger children.

Of course, old National Curriculum levels should be very old news. However, many music teachers have informed me that they are still required to use them for assessment and curriculum planning. Those who do not understand what a good music education looks like will cling to these dated standards, like the Japanese soldier who spent 29 years in the jungle after WW2. Continuing his fight long after everyone else had moved on, Hiroo Onoda refused to believe anything that wasn't a formal written declaration from his superior officers, and consequently did not formally surrender until 1974.

Many teachers are still required to give children a number showing how successfully they have met ‘age-related expectations’ (ARE) with no guidance whatsoever on what these ARE, well, are. A number 3 next to a child's name on a spreadsheet may superficially tell you that they are working ‘above ARE’. But it can only prompt more questions than any answers it gives: what are ‘age-related expectations’ in primary music education? How can you demonstrate this? How can the child show this (again, we come back to video evidence). Who sets the ARE? According to what research? Oh, it's for Ofsted? Why didn't you say so?

‘For Ofsted’ is no kind of reason

So much bunkum is done in the name of Ofsted. Written feedback in music ‘for Ofsted’. Books and written worksheets in music ‘for Ofsted’. Marking every single thing a child does ‘for Ofsted data’. This situation seems to be improving as schools catch up with 21st century thinking on feedback and assessment, but many schools are still operating on ancient Ofsted myths and misconceptions. Rimmer in Red Dwarf springs to mind – his family forced him to spend the whole of Sunday hopping instead of walking, due to a misprinted verse from Corinthians in their Bible which spoke of ‘Faith, Hop and Charity – and the greatest of these is hop’.

Firstly, the needs of children rather than the fear of Ofsted should be the prime motivation in education. If you are using an assessment system which slows down teaching and learning, and you can't see a direct benefit to yourself or the children you teach, you should be questioning it, as Ofsted certainly will. A common/historic Ofsted myth is that learning objectives need to be shared at the beginning of every lesson and ticked off as ‘assessment’ at the end. Ofsted even speak about this in their own literature. Have senior leaders read it?

‘It is not always necessary or most effective for learning intentions to be shared at length with pupils at the start of a lesson, particularly if this is done through detailed verbal explanations. Inspection evidence has shown that such strategies can delay pupils’ musical engagement.’ – Ofsted, Music in Schools: promoting good practice

Some leaders are still making everyone share learning objectives. If I shared learning objectives with children, it would be very odd. ‘Today, we are going to unconsciously experience semiquavers without naming them’. Also, a music lesson may cover so many objectives simultaneously that the entire lesson would be spent writing them into books! It's important to consider that Ofsted will no longer be making judgements on single lesson observations, but on a holistic picture of how music is delivered as part of the school's big picture. This is where strong leadership, guiding principles and curriculum are key.

‘The sequence of lessons, not an individual lesson, is the unit of assessment – inspectors will need to evaluate where a lesson sits in a sequence, and leaders’/teachers’ understanding of this. Inspectors will not grade individual lessons or teachers.’ – Ofsted, Inspecting the Curriculum

The onus is on the school, and therefore the senior leaders, to be purposeful, to take music seriously, to support staff in the delivery, and to think about the subject strategically in both the short and long term. I should say at this point that I am not associated with Ofsted, so I strongly recommend further reading of the following Ofsted documents, for yourself and your senior leaders:

-

Music in schools: promoting good practice – Guidance for teachers, headteachers and music hub leaders

Know thyself (and thy curriculum)

It would seem that teachers cannot uncritically follow a curriculum anymore. Too many school leaders describe their music provision as, ‘We use the Bingo Bongo Music Scheme across school and do trumpets in Year 4’. This suggests that they have taken easy options – all of the thinking comes from outside of school: the writers of the (fictional) Bingo Bongo scheme and the music service providing the instrumental service. Why are instruments always in Year 4′ Why just those children? How does it work? What are the visible benefits for the children?

Alternatively, music is taught simply to support topics with musical learning not considered e.g. songs about Vikings in Year 3. Beware. As chief inspector Amanda Spielman observes: ‘This is seen frequently in schools’ choices of musical activity where no thought has been given to how musical skills or knowledge are developed.’

Do we measure what we value? Or value what we can measure?

I have observed that untrained non-specialists will sometimes struggle to teach and assess musical activities. Instead they might revert to what they can do well – ‘Rosenshine the hell out of Beethoven’ (or ‘instruments of the orchestra’) and measure declarative knowledge about the topic with testing. While such knowledge may be useful, we have to take care that the tail is not wagging the dog. Procedural knowledge (i.e. musical skills) should be the prime driver in musical learning, and musical outcomes prioritised. Author, consultant and former teacher Tom Sherrington laments, ‘More powerful still, to my mind, is to focus more on developing teachers’ skills in questioning and giving responsive feedback during lessons. This is far more important than most marking but isn't given the same priority’. This is especially true in music lessons, where untrained teachers feel less confident in asking the right sort of questions and evaluating responses.

The Why Bird

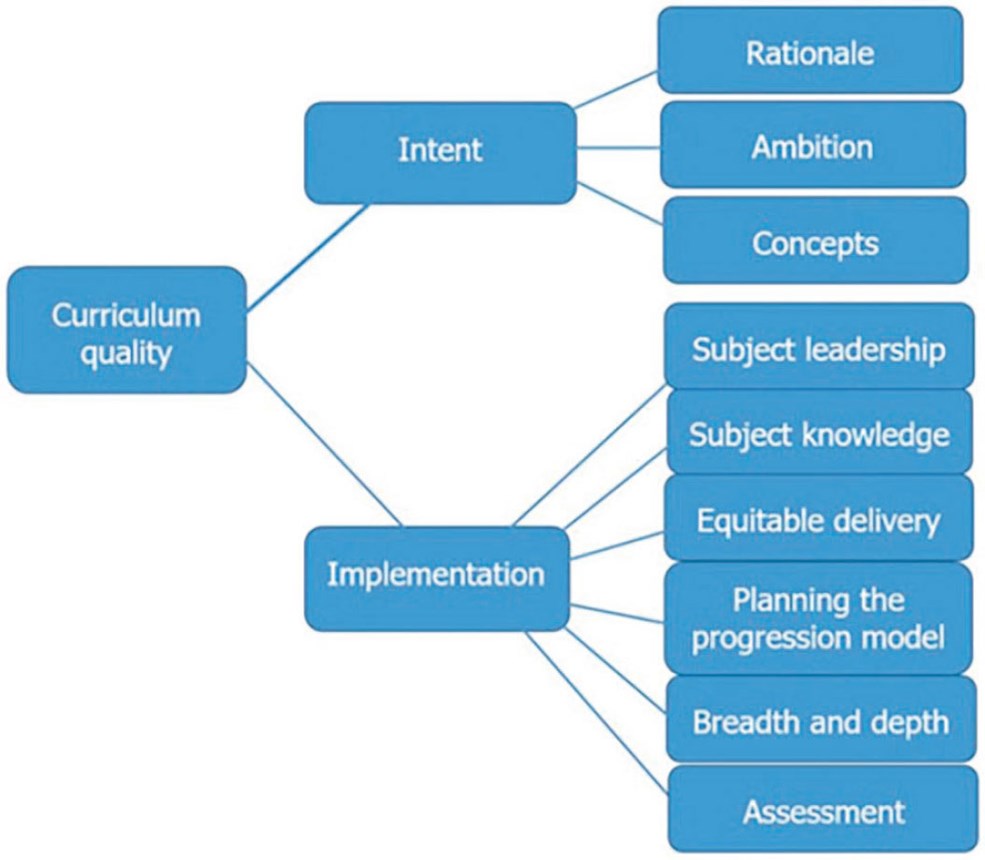

I like to introduce an imaginary ‘Why Bird’ to flutter around a school asking lots of annoying questions. Why this? Why now? Why are you doing trumpets in Year 4? (Intention); How is this being taught? According to what principles? (Implementation); How are you showing progress over time? How are you measuring success of the curriculum? Did it go as expected? (Impact). You can see how schools simply buying in ‘self-driving’ work schemes and external practitioners, or following topics, might struggle to answer questions about the things covered in the diagram below:

Last week somebody asked me why I was covering pentatonic American folk songs in the first term of Year 4, and I could explain how it built on previous knowledge, reinforced and revisited previous skills and unconsciously prepared skills and concepts for Year 5, and how each song had a purpose in doing this.

Makers of the Bingo Bongo Music Scheme may well helpfully provide such guidance, along with tracking sheets and objectives, but would you be able to answer a question about why children are studying ABBA songs in Year 3? How does this connect to the trumpets they do in Year 4? If this curriculum is your progression model, why have you chosen it? What benefits has it brought to the children? Are you measuring engagement, or development? Are senior leaders able to talk about it without a crib sheet?

A strong spiral curriculum will mean that curriculum elements are revisited to reinforce learning and ‘mop up’ anything that was missed. However, a problem with pre-set schemes of work is that they are static – when we measure impact and identify problems, can the curriculum be tweaked and altered, or tailored to the specific needs of children, according to your own professional judgement?

Looking ahead

There are, of course, teachers using very child-led approaches who may not have a prescribed curriculum at all. It is not necessary to plan out children's every move in advance, and much of what we do as music teachers is reactive and unplanned (children sing unexpectedly loud or miss a note). We may end up working on posture, instrumental techniques, or a specific chord progression, but we can still show, retrospectively, how we have sequenced that learning, and discuss the whys and wherefores of our choices (and what better way to show progress than with videos?).

If you are a ‘short-straw’ music coordinator and don't feel experienced, supported or confident in coordinating music across the whole school, and the subject is not given time on the curriculum, the judgement will not be upon you. Instead, inspectors will consider the whole school approach to the subject. What CPD or other support have you been offered by your school? What does the approach to music tell us about your school's educational values? If an overall judgement of the school is contingent on this, perhaps you could push any reluctant leaders to take your professional needs (and the vital needs and rights of children) a little more seriously.

Ultimately, we do what's best for the children and their development. I think as long as the school is trying to achieve this, as a team, with their music programme, nobody has anything to fear from Ofsted. It will be apparent without data and spreadsheets. Due to Covid delaying school inspections, expectations about how this will all pan out in the future vary. Some are hopeful that the focus on the quality of the wider curriculum and a move away from books and levels will see inspections reward schools who take the arts seriously and downgrade those that don't. Others point out that primary schools are still measured primarily on their English and Maths data, so while the goalposts may have shifted, the game remains exactly the same, and music will continue to be given short shrift. Time will tell.

Meanwhile, take musical development seriously. Devote curriculum time and long-term thinking to the subject. Develop and empower staff to deliver it regularly. Give it the attention it deserves with the best tools you can find. Film progression and pay attention to musical outcomes and how they can be improved upon, tweaking any planning accordingly. Then there is no fear of the deep dive. As Zoltan Kodály said: ‘Let us take our children seriously! Everything else follows from this… only the best is good enough for a child.’

Keep it Simple, Soldier! Teach music well and the deep dives will take care of themselves.

Jimmy Rotheram recently created a range of Teaching Primary Music resources for the Benedetti Foundation. They can be found at www.benedettifoundation.org/primary-music