Have your say: Letters to the Editor March 2022

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

Write to the editor at music.teacher@markallengroup.com and find us on Twitter @MusicTeacherMag.

Adobe Stock/ Vladwel

Quality assurance

In his recent MU column (MT January, p.39), Chris Walters discussed the challenges faced by visiting music teachers, and made reference to the Level 4 Certificate for Music Educators (CME) as ‘a new qualification for VMTs’ and as something which ‘never really took off.’ Unfortunately, neither of these statements is quite correct.

As outlined in the National Plan for Music Education (NPME), the CME is ‘a music educator qualification… ensuring the wider music workforce is better skilled, and properly recognised for their role in and out of school.’ At our centre alone, the Trinity CME has benefitted a vast number of music educators working in early years, primary classroom and instrumental delivery, community music, and private tuition.

I know that there is a large network of other Trinity CME centres reaching even more music educators, including a highly well-regarded programme for early years practitioners run by CREC. The qualification has gone international in the last couple of years, and now benefits educators in schools, early years, and private practice on every continent except Antarctica (the penguins being sadly not all that interested in pedagogy.) This is in addition to the ABRSM's version of the CME qualification, which also has its own network of centres.

This qualification is aimed at everyone working in music education, and while I agree with Chris – based on our own experience as a centre – that the take-up specifically from music education hub-employed VMTs has been comparatively low as a percentage of the total, that by no means supports the statement that the CME ‘never really took off’. As a centre, we have seen particular value in the CME in reaching educators who need the qualification most. The lack of entry qualifications makes it ideal for those who do not have formal qualifications, or who are beginning a second career in music teaching. VMTs working for hubs often have access to regular training (whether they take this up or not is another matter!), but private teachers working alone or community musicians working outside of a network have limited options. Even primary teachers and teaching assistants – who are offered all kinds of CPD at schools, often on a weekly basis – often struggle to find anything that develops their subject-specific skills in music.

At a time when the NPME is being refreshed, we should be championing the CME qualification to ensure that its unique benefits are properly recognised. I agree with Chris that funding for the qualification should be readily available, and that is something which I hope the panel will consider as they rewrite the plan.

Dr Elizabeth Stafford, CME programme leader, Music Education Solutions

Chris Walters responded:

I am grateful for Elizabeth Stafford's comments; saying that the CME ‘never really took off’ was incorrect. I should have said that, in my opinion, the CME has not met its stated aims because the policy behind it was never properly developed.

The idea of the CME first came up in the government's Henley Review (2011), which stated: ‘A new qualification should be developed for music educators, which would professionalise and acknowledge their role in and out of school. […] It would be as applicable to peripatetic music teachers as it would be to orchestral musicians.’

The NPME then developed this idea: ‘A large proportion of the music education workforce, such as peripatetic music teachers, are based outside school. These professionals need to be recognised for their work and have opportunities to develop their practice. To facilitate this, […] a music educator qualification [will be developed] to ensure the wider music workforce is properly recognised for their role in and out of school.’

Others may disagree, but to me these statements suggest that the new qualification, which would become the CME, was primarily intended for the peripatetic workforce, in response to the well-known lack of training and qualifications for these teachers. Even if the CME was not meant for peris above other teachers – and as Elizabeth rightly says, its uses are broader – we should still ask what it has achieved for this group, since these teachers are the backbone of hubs and therefore of the NPME.

The CME is an excellent and flexible qualification (disclosure: I worked on its development and roll-out). However, it does not lead to any kind of qualified teacher status or advancement in pay; teachers usually have to pay to take it; and centres offering it need to come up with their own funding or business model. It is testament to the CME and those delivering it that it still offers value despite these obstacles, which are the result of underdeveloped (or rather non-existent) policy.

I agree that we should celebrate the CME's unique benefits, but if it is to reach teachers in any significant numbers (Ofqual data reveals that numbers are a tiny proportion of the workforce) then the policy behind it needs a major rethink – or just a ‘think’. Policymakers should consider what training they believe our peris are entitled to; what qualifications they expect of them; and how to reward ‘qualified’ teachers through status, progression and pay. We will see whether these basic issues are addressed in the ‘new’ NPME when it's published.

Chris Walters, national organiser for education and health and wellbeing, Musicians’ Union

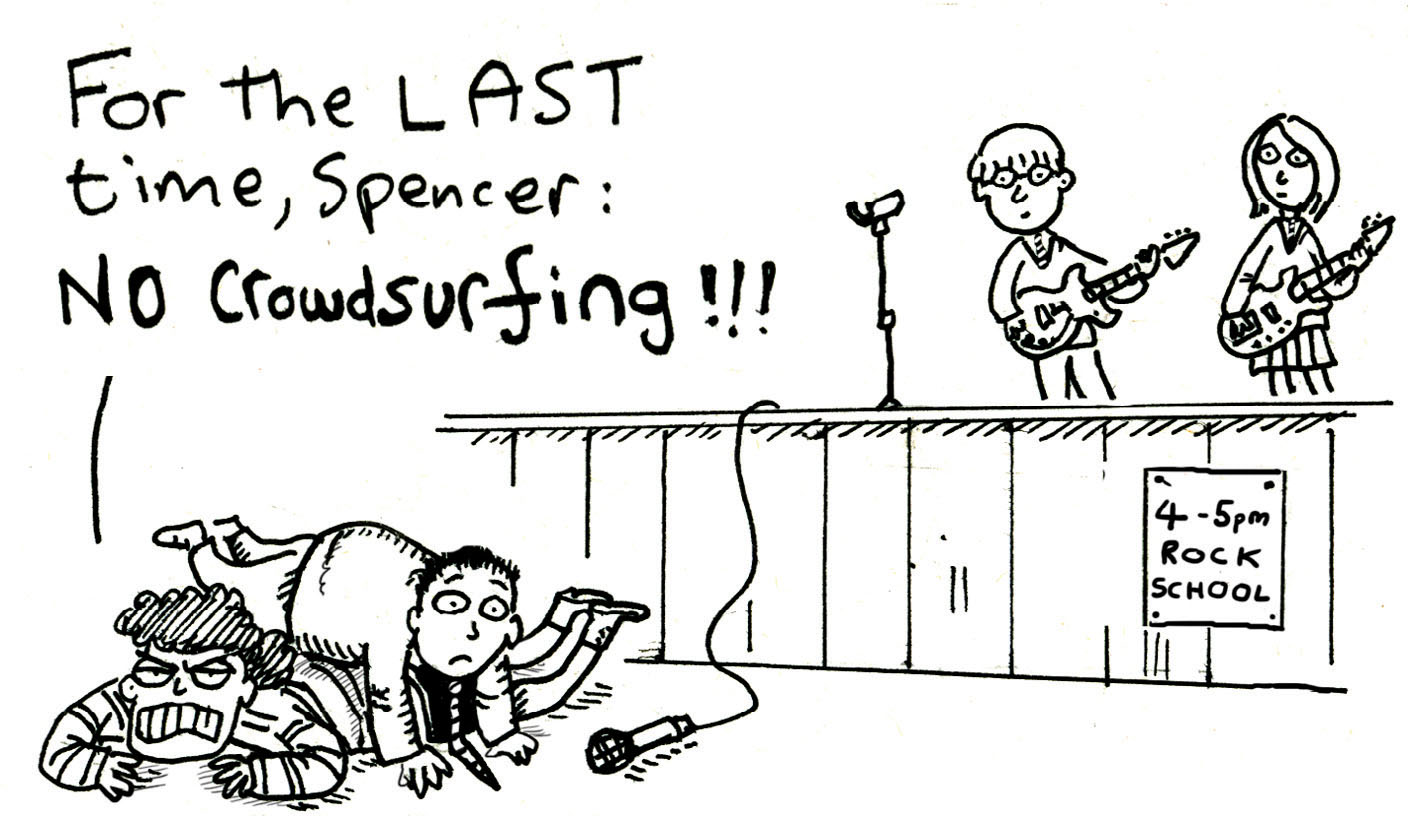

THE PERIS by Harry Venning