Putting pencil to paper? Teaching composing in schools

Sunday, May 1, 2022

The theme for this month's issue is Music Technology for Composition, so we asked readers for their thoughts on notation software, composing with pencil and paper, learning notation, and everything else that comes with this. Here, six educators share their views.

Kuznietsov Dmitriy/Adobestock

No method off-limits

There are so many ways of making music, and children should discover – through play, through experimentation, through education – what works best for them. Nobody should be forced into ‘primarily’ using any one method of engaging with music, and instead, they should be encouraged to discover for themselves what their preferences are.

I think children should definitely be given the opportunity to learn how to read music. However, it is important to be aware of the limitations too. Standard notation allows us to access the music of Stravinsky but is less effective at helping us understand SOPHIE (for example). I think children should also be given access to digital audio workstations (DAWs), and they should learn how to record their music, improvise, interpret graphic scores, and so on. No method should be off-limits.

Often, I set my students composition tasks that can be completed in any number of different ways. They are in charge of their own creative process. Students from classical backgrounds sometimes opt for Logic (DAW) while students from rock backgrounds often choose Sibelius (notation programme), contrary to what we might expect. The only thing that really matters to me is that my students are developing their skills and enjoying themselves. Notation is but one way of achieving this.

Professor Ben Gaunt, associate professor in composition, Leeds Conservatoire

‘Notation dependency syndrome’

Most kids, especially before adolescence, are bursting with creativity and a desire to explore. It's part of the same drive that taught them to talk – they often want to ‘babble’ musically, which involves some imitation as well as sonic and kinaesthetic experimentation. Tragically, there's a tendency for educators to shut down these explorations because they tend to be noisy and unstructured.

To me, this is the beginning of ‘notation dependency syndrome’ – the inability for some musicians to function in any musical situation that doesn't present them with a five-line staff and very specific instructions. When students are asked to compose on a staff before they're ready, they inevitably end up ‘painting’ notes without having any idea how they sound. This can be a fun exercise, but it's not a way to develop musicality.

Here's how I see it: a staff is a graph of a scale. A scale is a pattern of melodic motion. A melody is something we sing. Imagine dropping kids two levels deep into abstraction with literally anything else. We don't make kids learn Eshkol-Wachman movement notation before they can make up their own dance moves. There's so much to explore that's directly available to beginners: dynamics, register, texture, density, rhythm, timbre, form. These are all core aspects of music-making that shouldn't have to wait for a highly specialised visual language.

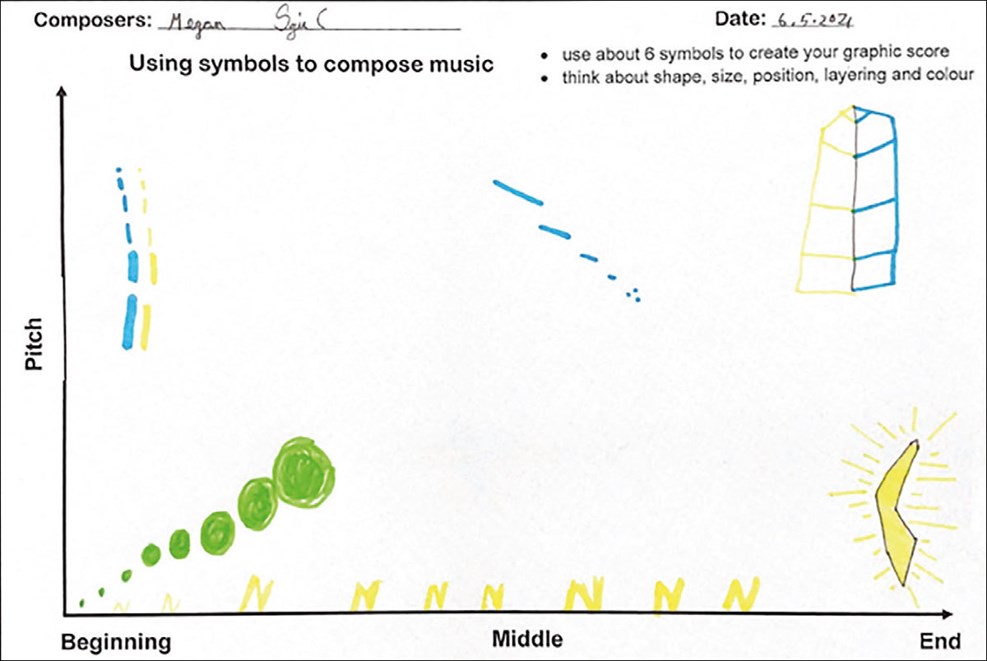

Improvisation is a core component of many, if not most, of the world's musical practice, and it's a natural drive for kids. ‘Teaching composition’ should simply be a matter of helping learners expand and sculpt their improvisations until they like something enough to want to do it again. At that point, graphic scores are terrific—they can provide a mnemonic map for a composition. As the desire for specificity grows, the student may discover the utility of the staff. Now, instead of a visual gatekeeper, the staff can be an ally in musical expression.

Nate May, composer, pianist, educator

Composition of the body

There is a music classroom I have seen recently in which the only notation referenced is this: ‘Rhythmic notation uses counting and pitched notation uses the alphabet’.

If we only boil notation down to elements, we miss the whole point of the purpose of notation, which is to communicate and leave degrees of space to interpret and bring ourselves to the score. Music comes ‘from us’; through the voice, body percussion, and use of instruments. Instruments are played with bodies. Notation is also itself a physical act; mark making is vital and I introduce mark making to connect sound to symbol in early years music lessons.

What is essential, in my view, is that before we have composition of the cerebral, we have composition of the body – that the body understands form, gesture, and articulation first, and this can be the starting point for composition. I am a certified Dalcroze Eurhythmics teacher, and it is the philosophy of ‘sound before symbol’ and experience of music through the body that I use as a starting point for composition.

I have done projects in which children, inspired by an image or piece of text, create a piece in movement that has all of the elements you would experience in music: form, phrasing, articulation, rhythm, metre, gesture, texture, silence. Levels of pitch can be shown through movement. This is refined, rehearsed, and performed, and then the next element is to play on instruments the piece realised in movement.

I call this work: moving into composition. I have used this kind of methodology when creating my own solo compositions. Find a starting point; move it; play it. This way, either in group or solo work with children and adults, there is an element of the composition truly coming from the self. Music cannot be reduced to alphabet and counting – this is not music; it is a barrier to truly unleashing creative composition. I am also inspired by graphic scores, those which give agency of interpretation.

I think much music relies far too much on texts and scores, and I would love to see more musicians being relieved of the page and perform works as dancers and actors do without the limitations of paraphernalia. I encourage everyone to work through the body into composition.

Mary Price-O'Connor, The Moving Theatre Lab

A graphic score created by a pupil at Howell's School in Cardiff as part of a project facilitated by Ruth Coles and the Berkeley Ensemble

Waiting for something to click

Views around the use of technology to aid music composition in the classroom often vary dramatically. They vary from: ‘It's the perfect tool to enable pupils to hear their work and keep them motivated in a stimulating and practical setting (the sort of instant gratification they are used to)’, to, ‘it negates the careful and methodical approach to compose effectively. If Beethoven – deaf for much of his composing career – managed without Sibelius (other notation software packages also available) then can't we all?’

There is no question, then, that the use of technology for music composition is somewhat of a double-edged sword; its uses – not only specifically to the pupil, but also in empowering teachers to manage potentially large groups of pupils more effectively – are patent. But while it provides a valuable tool for instant aural feedback, flexibility, and clean presentation, does it encourage pupils to disregard important theoretical steps? Or the importance of working in a methodical way? Therefore, like any aspect of a teacher's planning and learning, each step should be carefully considered and thought through.

For me, the overarching consideration of using notation software is to clearly establish from the outset for which part of the composition process it can be of use. It is important that pupils have a basic understanding of the fundamentals of melody and harmony, dependent on their age and ability, and that technology doesn't become a misleading proxy for this knowledge, where pupils are left ‘swimming aimlessly’ waiting for something to click. That is not to say that notation software might not be used to produce objective worksheets with specific focus for individual tasks; rather that in more creative settings, this technology is not utilised as a blank canvas on which all technical and creative work is expected to be made.

Another unquestionable benefit to notation software is its flexibility. Whether through making changes tidily (imagine an average pupil's overall composition process if completed entirely by hand!) or being able to try out different composition devices efficiently. For example: ‘Try a dominant pedal instead here; have you considered reharmonising this chord? You could add a lovely call and response section here.’

Focusing more on GCSE and A Level pupils, the ability to copy key ideas later in a piece and consider different developmental devices is also useful. This flexibility goes hand-in-hand with productivity, and enabling pupils to complete more high-quality work can only be a good thing. A potential drawback of a notation software's flexibility, though, is the cursed ‘cut and paste’, which sometimes yields a false sense of progress or meaningful development, and one that pupils find difficult and disheartening to have to rectify.

That said, one should not assume a Western classical perspective; there are many music styles in which repetition is an effective idiomatic feature of the music, and technology's flexibility in the context of texture is especially beneficial. The flexibility to develop and refine textures is another area in which technology wins hands down.

Although notation software is an excellent tool for producing music theory and composition worksheets, it can also be used as an effective means of scaffolding – from broad approaches such as labelling sections of a sonata form piece, complete with labelled sections, to more detailed notes being applied. I even find that subtle approaches such as laying composition templates out with four or eight bars per line helps encourage pupils to think in balanced phrases, if this is the intention.

We all know the importance of feedback, and many notation software packages allow either dedicated commenting, or the input of text, which can be used to provide informative and specific feedback. This provides a clear sense of progression for pupils, the pragmatic nature of which helps to balance the more holistic nature of creative composition, which can all too often leave pupils feeling stranded. Composing templates and the effective use of feedback also help to mitigate against the potential for ‘losing sight of the bigger picture’ – perhaps an inherent result of composing with technology, when notation software tempts pupils to work on detailed textural aspects of their work prematurely to the determinant of an effective overall structure.

Confidence is a huge part of pupil success, not only in music composition but across all aspects of personal development, and technology, carefully planned and applied, can empower a child with a real ‘can do’ attitude. It is much better for a pupil to get something written, even if it needs feedback and subsequent refinement, but there is always a balance to be found.

While there might be times when a more holistic approach to the use of technology in creating music is appealing – arguably more so with younger pupils – the key is to plan carefully and ascertain exactly what parts of the process technology is enhancing, so that it is a tool and not a master. To quote the ancient adage ‘with great power comes great responsibility’, the responsibility lies with the teacher, which can then yield the power for the pupil to compose effectively and enjoyably.

Mark White, music teacher and head of music technology, Wells Cathedral School

Credit: Chris/AdobeStock

Composing or composition?

We are thinking about composing in this issue of Music Teacher. Or are we thinking about composition? Is there a difference? I would venture to suggest that there is, and, what's more, that this difference matters. Composing is a process, it is about ‘doing’, and in the national curriculum, this is where the emphasis is placed – on the ‘doing’.

Composition, on the other hand, can be both a process and a product, it can be ‘doing’ or ‘done’. But more than this, the word ‘composition’ carries a lot of baggage with it, and this is different baggage to composing; think of composition exercises, composition classes, these are concerned with a Western classical notion of what it is to be a composer. But composing is a broader construct; it can, or maybe should, encompass a wide variety of musical styles, types, and genres, and, importantly, is amenable to both progress and improvement.

The question also matters because it is about how we as music educators deal with teaching and learning composing. Let us take the case of composing using computer-based music software that looks like traditional staff manuscript paper. I have seen many examples where pupils are sat at a workstation and told to compose. This is in some ways like having your first driving lesson, and the driving instructor says, ‘I am going to give you a mock driving test now’. This is before you have learned what the clutch does, how to change gear, or anything.

Clearly, this would be daft and dangerous, but the analogy is that the learner is expected to drive; in other words, produce a product. The link to composing is that it is the outcome that is prioritised; not the process by which the learner reaches this. Learning to drive is like learning to compose; we can't just expect the outcome to be reached with no teaching.

It may seem like this is a far-fetched scenario, but as a profession we do need to think about pedagogies for composing. After all, what creating music is likely to be is very different across the Key Stages, and learning to compose, and, importantly to make progress at composing, should also be very different. We know a lot about performing, both in specialist and generalist settings, but the same is not true about composing, sadly.

For many years I have been working on a research project called ‘Listen Imagine Compose’, with colleagues from the organisations Sound and Music and Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, and this continues to look into the teaching and learning of composing, and associated pedagogies across Key Stages 2-4. There is much still to be learned, but the project has already shown us many things, one of which is that this is a complicated area. Meanwhile, we as educators need to think about the language we use, and the baggage it carries with it. Composing or composition, process or product – which is privileged in your thinking, and your teaching?

Professor Martin Fautley, Birmingham City University

Starting with shapes

For those beginning to compose in the early stages, I suggest the following:

- Encourage children to enjoy the look of music on the page and, as soon as possible, write down what they play and hear, even if this is, at first, just shapes. Notating phrase shapes/contours (how high and low a wavy line goes and the distance between peaks and troughs) is more important than individual notes.

- When dealing with notes, it is the intervals between them that matter. Any line can be transposed. Use a contour as described in the point above, and copy/trace it onto a graph (x and y axes) with pitch names written on the y-axis and the x-axis showing the time/duration in seconds. This begins to help the pupil relate sounds in time, as well as a feeling for texture/density and vertical in conjunction with the linear.

- The problem with using a computer too soon is that programmes tend to restrict notation to pitch and rhythm in a conventional way. If access to more advanced technology is available – showing sounds visually and aurally in a graphic manner (frequencies, densities and so on) – then this is also excellent.

- The intervallic approach described in point two can be used to introduce a pupil to scales and modes of varied types (for example, not just major and minor). An excellent delineation of this is available in Chapter Two (Scales) of Twentieth Century Harmony by Vincent Persichetti, published by Norton.

- Taking a cue from Hindemith's training books, all exercises/little pieces should be sung. This really helps a pupil internalise shapes and intervallic distances and character.

- Discuss with pupils what makes a melodic line have a sense of direction (towards a cadence, although the latter does not have to be conventional).

- Two-voice counterpoint (treble and bass) is much more useful than ‘chords’ when tonal harmony begins to be addressed, especially in relation to point six.

- Make each piece (rather than an ‘exercise’) different and try to ensure real character in as many ways as possible.

Robert Saxton, composer

If you'd like to share your thoughts or respond to any of the views here, please write a letter to the editor at music.teacher@markallengroup.com.