Helping students become comfortable with DAWs in music lessons can be both enjoyable and rewarding, though it may feel overwhelming for students with varying musical abilities and levels of experience with technology.

My philosophy for using DAWs in my teaching has always centred on exploring their benefits as teaching aids and bridging the gap between musical abilities and experience with music technology. Having used DAWs for the best part of 20+ years, I have developed a relationship similar to my instruments, finding tips, shortcuts and learning methods to inspire new musical ideas and approach challenging material. As Andrew King states, ‘the more intimate the relationship between body and technology, the more the technology becomes an inactive interface between musician and music’ (2016, p. 44).

I always encourage my students to approach DAWs like learning an instrument and hope that in time they will develop the confidence to interact with the software, and bridge the gap between creativity and what can be realised.

Here are some tips and hacks to help your students become comfortable using DAWs in your classroom.

1. Find the right DAW for your students

Choosing the correct DAW is crucial for the music-making experience you want to provide. Options range from user-friendly programs like Chrome Music Lab, aimed at beginners, to intermediate options such as Soundtrap, Bandlab and GarageBand, which offer more choices for editing and programming. For advanced users, DAWs like Pro Tools, Logic Pro X, Ableton Live, and FL Studio provide all the necessary tools for mixing, editing, producing and mastering music professionally.

You must consider how you will implement DAW in your teaching. In a previous school I worked at, some of my students struggled with notation on Cubasis but thrived with Sibelius. At my current school it's the reverse, though we use GarageBand/Logic Pro. Personally, I lean towards GarageBand/Logic because of my long experience with them, dating back to Logic 5 Platinum on the PC. Learning how to program MIDI, working with destructive and non-destructive audio editing, and using the Arrange window allowed me to learn orchestration and arrangement without relying solely on notation; in fact, using Logic 5 helped me read notation!

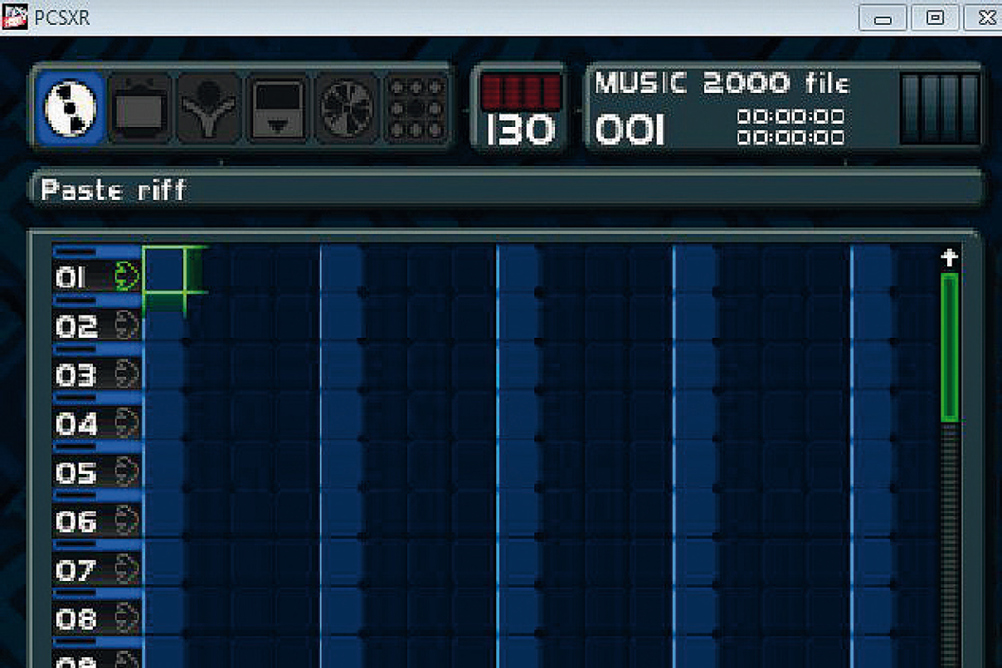

Selecting the right DAW impacts your students' initial experiences, especially if it is their first encounter with making music using technology. My first experience using a DAW was on a PS1 game called Music 2000, where I learned sampling through a console controller. This game provided the foundation for using DAWs and helped me transition to more advanced programs like Cubasis VST and eventually Logic, allowing me to adapt quickly, even to Pro Tools.

In addition to popular DAWs, consider these lesser-known applications suitable for teaching beginners to intermediate users:

- Creatability (online, no download required). This is a collection of apps that use web and AI technology aimed at the accessibility community and the use of kinesthetics to use the apps. I highly recommend ‘Body Synth’ and ‘Word Synth’.

- Learning Music (online, no download required). Created by Ableton, this program is perfect for those not yet ready to use full DAWs. It breaks down elements of music using technology into user-friendly apps. It is a great learning tool for synthesizers, beat mapping, filters, envelopes, etc.

- Soundplant (download required). This live audio sampling app allows you to use your computer keyboard to trigger samples. Though limited, it's accessible and easy to use for beginners.

2. Slow down to speed up

When helping students with challenging keyboard parts, the ‘Slow down to speed up’ technique was a game-changer for me.

I start by getting students to slow their project's tempo to a level they find comfortable playing to. Remember to include the click-track, as they will need that to quantise. Rehearse the parts as normal and then record to tempo. After recording, quantise and increase the tempo back to the original.

This method may seem simplistic, but it has helped my less-confident students create music without feeling like they cannot play the keyboard. It alleviates the pressure of achieving the perfect take, allowing them to hear their contributions as intended. It enables more productive lessons, as students can focus on recording their ideas quickly. Some may view quantising as a crutch, but I liken it to the auto-correct features in MS Word: those blue and red squiggly lines are there to help you correct mistakes! To further challenge students, consider giving different tempos based on keyboard skills.

3. Build like Lego

This next tip draws on my research and a previous article for MT on teaching improvisation in secondary schools (MT June 2024), and on James Ingham's MT article on scaffolding improvisation (MT October, 2024).

Start by getting students to create an improvised melody or chord progression of at least 8 bars. Using a click-track or previously recorded sections, students improvise a melody that follows the theme of the composition; at this stage, mention that the melody is not assigned to any particular part. Encourage them to play without fearing mistakes; any ‘wrong’ notes can be deleted/amended later in the piano roll. After recording, listen back then quantise.

Using the split/cut edit on your DAW, get students to edit their part into segments: 2-, 4- or 8-bar phrases. They can then manipulate these phrases to create ostinatos for other tracks, arrange them to form instrumental parts, or develop counterpoint harmonies.

A BTEC student's work using the ‘Build like Lego’ method. We split the melody for flute and oboe

A BTEC student's work using the ‘Build like Lego’ method. We split the melody for flute and oboe

I had a eureka moment with one of my GCSE students last year when I asked them to create a 16-bar phrase. Rather than recording the whole thing at once, they chopped the melody into 1- to 2-bar phrases and then rearranged the order of melody, allowing them to construct something modular and compose using a melodic structure.

4. Use audiation

Audiation – creating meaning from sounds based on prior knowledge – was significant in my helping students connect with music-making using DAWs. During a lockdown lesson on musique concrète, I had to think of a way to model how effects can alter sound characteristics and enhance samples, without modelling in the same room. Using Soundtrap, I listed the effects that were most popular and guided them to think musically about how each effect altered the sound. I posed questions such as:

- ‘Does this [specific] instrument remind you of a song or creature?’ (whether through timbre or genre)

- ‘Where might you commonly hear this effect in real life?’ (in relation to reverb and delay); and

- ‘How would you describe the changes this effect brings to the sound?’ (in relation to distortion, chorus, panning)

An example of feedback and use of audiation; the nature references build on work using forest sound effects in musique concrète

An example of feedback and use of audiation; the nature references build on work using forest sound effects in musique concrète

Using audiation, students engaged in sound manipulation and melodic composition. In demonstrating how reverb made it sound like they were in a tunnel and how distortion could produce a fire-like effect, I encouraged students to think musically about why we might use certain effects and about atmosphere. This approach made it more intuitive for students to use effects and indeed compose parts. I received insightful comments on their work, such as ‘That reminds me of Harry Potter!’ (3/4 meter played on a glockenspiel sound), ‘That feels like it's underwater!’ (using chorus with a low-pass filter), or ‘I wanted the voices to sound like they're on a phone!’ (using EQ).

Conclusion

DAWs should not replace traditional instruments in your students' music education. Instead, they should facilitate their imagination, as ‘music technology is the key to unlocking the hibernating musician within’, in the words of Adam Bell (2015, p. 48).

Using DAWs can be complicated, but I hope my tips and tricks can help you bridge gaps for those who don't play instruments, or assist students with larger projects such as orchestrating and arranging.

Links and references

- Bell, A. P. (2015) ‘Can we afford these affordances? GarageBand and the double-edged sword of the Digital Audio Workstation’, Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 14(1).

- King, A., Himonides, E., and Ruthmann, S. A. (2016) The Routledge Companion to Music, Technology, and Education. Routledge.

- Creatability: experiments.withgoogle.com/collection/creatability

- Learning Music: learningmusic.ableton.com

- Soundplant: soundplant.org/about.htm