‘Improvisation is the most widely practised of musical activities and the least acknowledged and understood’ (Bailey, 1993).

This maxim loomed large as I stared at my laptop screen in 2020, wondering how to begin to assess my students' improvisations. How did my own lecturers assess my final recital? How do audiences assess a good improvisation? Would it be fair to model improvisations on existing ones? If so, which ones – Paul Gonsalves's 27-chorus masterpiece at Newport, or Cory Henry's iconic solo on ‘Lingus’? (Perhaps I will avoid Nick Jonas's solo at the Country Music Awards!)

Improvisation assessment basics

Before developing my improvising pedagogy, and before considering assessment rubrics, I made a list of considerations. Any improvisation assessment must:

- Follow departmental and/or national guidelines for other music-making, i.e. performance, composition, etc.

- Give students/parents/department a sense of purpose in achieving termly goals.

- Be easy to follow when grading.

- Be flexible enough to allow different skills to flourish, i.e. use of rhythm, phrases and phrasing, melody, etc.

- Have clearly defined learning objectives on which to grade.

How to assess improvisation

I then began to think about how students present their work and how to assess it authentically. If students are presenting a solo over a backing-track or performing in a duet, how do I assess paired work if one is improvising a chord progression and the other a melody? If it's an ensemble, how can the soloist be assessed via their interaction with the rest of the musicians? But I realised this would be problematic to plan for and, instead, I settled on some easy points to use:

- Regardless of the improvisation context, assess it like any performance/composition.

- Use existing frameworks from previous assessments of classwork and adapt language to fit improvisation.

- Split the improvisation assessment into melody, harmony, phrasing (timbre, dynamics and articulation) and structure, underpinning all with rhythm.

Outside help

A good place to start was exam board provision such as ABRSM's Jazz Grades and Trinity's Teaching Improvisation. Both boards offer detailed paths into how they prepare students for improvisation by describing different improvisational contexts and a step-by-step guide to developing skills. ABRSM's Practical Musicianship is also helpful for wording, if you want to offer reasons for a grade. The Practical Musicianship exams also encourage interconnected development of ‘musical listening, reading and playing skills through a holistic approach’ (ABRSM, Practical Musicianship 2019), with musicianship skills relating to improvisation as ‘the ability to internalise music and to reproduce it’, ‘interpreting written music with minimum preparation’, and ‘exploring the possibilities inherent in a short motif’. This could allow you to use notation with your students so they have something to work from.

You could also use the ISM model of improvisation, adapted by Jane Werry and championed by MTA committee member Alex Parson. This suggests:

- Improvise a basic response to given stimuli.

- Improvise with some musicality with a range of options.

- Improvise appropriately, musically and with stylistic integrity.

If creating rubrics from this model – from what seems a clear outline – I might base my assessment on the following:

Facilitating improvisation

Facilitating improvisation

As for instrumental/vocal assessment, does it matter that your students also show good or correct technique? Let's take the keyboard: I have students who have never had piano lessons, have SEN and only started learning classroom music since joining me in Year 7. Before our improvisation project, they struggled with technique and getting to grips with the keyboard layout; so going into this, I knew that I would be wasting time trying to correct their technique. After our project, their technique improved, and they gained confidence in expanding their keyboard range.

In the Youtube clip youtu.be/YCinKm5B3cI you will hear that students were able to improvise both chord progressions and melodies with fluidity and a good level of melodic and rhythmic skill.

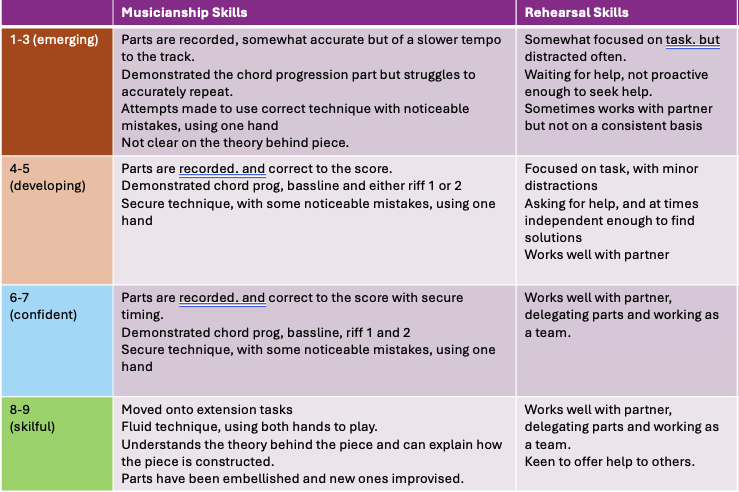

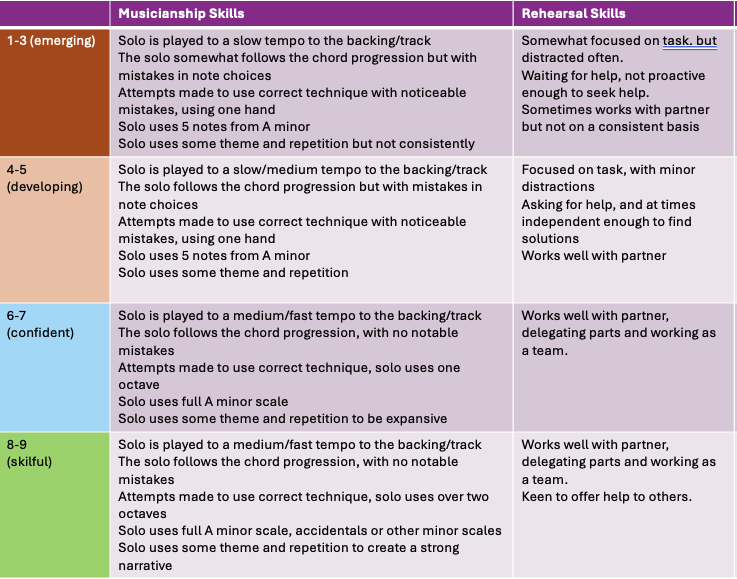

Inevitably, some flexibility is required when isolating and measuring the components. In the next tables, we see: (a) an example of how I adapted a Year project for ‘Shape of You’, with students using GarageBand to recreate the song; and (b) an example of how I would adapt my existing ‘Shape of You’ assessment to an improvisation assessment model, based on students improvising a solo melody over a chord progression using keyboards (other instruments can be included).

Rubric for assessing a Y9 project recreating ‘Shape of You’ in GarageBand:

Rubric adapting the Y9 project to an improvisation assessment model:

Note how I built up the skill level, but kept elements such as technique the same throughout all stages. I also included rehearsal skills, as this is crucial to how students develop as improvisers.

When doing peer assessments, I draw upon students' ability to ‘think in sound’ after their rehearsals, reflecting on what they felt was successful in their improvisation.

Formative or summative assessment?

When I teach improvisation, both in class and rehearsal rooms, I always feel that I need to include summative assessments, more so than I would typically do, often while getting feedback from students. Perhaps this is a way of ensuring they stay the course and remember why they are learning this skill!

Formative assessments, though, also help students develop improvisation skills. When done correctly, it's wonderful to hear conversations about how one could try playing certain notes instead of others; or how ‘Sir’ said it was okay to leave gaps (i.e. thinking time) as ‘that Trumpet dude did on “So What”.’

This will sound clichéd, but in assessing improvisation, the journey matters more than the destination. A summative assessment allows us to put a full stop to learning, but I see it more as a comma, given the flexibility that using improvisation skills can allow for other topics in your schemes of work. Assessing students' improvisation should be done over time, using those moments of micro-assessments to let them know of their development. Let us not forget that your students will have no clue about their progression at first, unlike an instrumental/vocal skill which can be quantified via technical progression. By creating peer and teacher assessment opportunities, you are teaching/modelling what good improvisation is, or permitting students to create their ‘improv vocabulary’.

When to relax control

Assessing improvisation in curriculum music creates a duality between what we teach (control) versus students' ability to explore (with lack of control). How much control is one willing to forgo if regarding what students learn? What if all that effort leads to an assessment that produces nothing more than random keyboard bashing that could be palmed off as creativity?

Jutifications for improvisation assessment

Assessing improvisation must allow students to take ownership of music-making and express themselves beyond demonstrating musicianship skills, as argued by Daniel Healy and Kimberly Lansinger Ankney (2020). One needs to facilitate students' ‘musical improvisation experiences’, they point out, as a product of developed improvisation pedagogy and in support of the curriculum.

Improvisation pedagogy must be at the same standard as other secondary music subjects and as expected in general education, Tony Wigram has argued (2004). Improvisation, therefore, must exist on the merits it brings to secondary education; this might explain why it is mainly absent from secondary education. The outcome of improvisations is in the hands of our students and what they produce is out of our control, to some extent.

Perhaps improvisation's reputation among educators and academics places it in a ‘soft’ justification category of secondary education, in contrast to ‘hard’, measurable activities. The perception of improvisation may be to promote holistic qualities that are at odds with academic rigour and at odds with the measurement-based model of attainment in secondary education. This is the view of authors Chris Philpott and Gary Spruce, for example, and could explain why music educators may not value the skill of improvisers as highly as that of composers or performers (see Debates in Music Teaching, p. 58). The last two are easily quantifiable, and less subjective when it comes to grading, in my opinion.

Assessing improvisation

The purpose of assessing improvisation should be as per any other musical skill discussed in your department or practice. The assessment must be authentic, robust and measurable to inform and help students develop their musicianship skills.

Creating assessments for improvisation may be new to some readers; accept that the first ‘go’ of your formative/summative assessments may have some growing pains. Utilising formative data on students' progress may help refine the summative, as you may notice trends and patterns in their output, which you could use to tweak what they need to demonstrate.

References

- Bailey, D. (1993) Improvisation: Its Nature And Practice In Music, 2nd edition. Da Capo Press.

- Healy, D. J., and Lansinger Ankney, K. (2020) Music Discovery: Improvisation for the Large Ensemble and Music Classroom. Oxford University Press.

- Wigram, T. (2004) Improvisation: Methods and Techniques for Music Therapy Clinicians, Educators and Students. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Philpott, C., and Spruce, G. (2012) Debates in Music Teaching. Routledge.