Emotionally in tune: Clare Hammond

Harriet Clifford

Monday, March 1, 2021

Pianist Clare Hammond's educational plans for her new disc, Variations, may have been momentarily thwarted by the pandemic, but here she tells Harriet Clifford about how adversity in her own life reminded her of the emotional and communicative power of music.

Julie Kim

Children don't feel that there's a barrier with classical music,’ says pianist Clare Hammond, compellingly eloquent and softly spoken, even through Zoom. ‘It's obvious sometimes that some of the kids have never heard this kind of music before, but they can always relate it to the music they do know. They don't see any difference between what they hear on Britain's Got Talent and what I'm doing – it's part of a continuum for them and they haven't boxed if off yet.’

This is surprising, perhaps, considering that Hammond's career has been self-professedly distinct in that she programmes a lot of ‘unusual repertoire’. Alongside the standard Beethoven and Rachmaninoff, she will also include contemporary music or music by historical composers who are less well known, such as Hélène de Montgeroult.

‘I think the more we can do to stop that boxing off, the richer [children's] music experience will be throughout their life. They'll have a broader range, and we'll be able to share this wonderful tradition.’

Putting down roots

Since moving to the area in 2017, Hammond has been performing in local, largely underprivileged, primary schools in partnership with Gloucestershire Music, a string to her professional bow which came about because she wanted to ‘put down roots’ and feel part of the community. ‘That's one of the perils of being a travelling performer – the previous place we lived in was lovely and we had some great neighbours, but I was travelling and couldn't interact with people on a regular basis.’

After giving birth to her second daughter in December 2017, Hammond suffered from severe postnatal depression. ‘I was ill for quite a long time and that was a scary period. Obviously, I was miserable a lot of the time, but the really scary thing was when I lost contact with rational thought.

‘Part of that was a heightened emotional response to guilt. I started experiencing this guilt which was just off the scale, and it was so extreme that to even call it guilt seemed strange because it was so different from a normal experience. I decided I just needed to do something to connect with people and to feel like I was giving back.’

Having tried, rather simply, sewing, baking, and art to aid recovery from my own depression in the past, I can't help but be impressed when Hammond humbly explains that her postnatal depression pushed her to give performances in prisons. She describes the concerts as her ‘lifeline’, which ended up having a greater impact on the audience members than she initially expected.

Analytical thinking

‘Prison concerts had always been in the back of my mind. As a student, I did a mentorship with the French pianist Anne Queffélec and she did concerts in prisons in France. I'd always been too scared to do it before because I was worried that I may be playing to an audience who didn't know much about classical music and they'd just think I was ridiculous and irrelevant.

‘I decided to just take the plunge and the first concert actually turned out much better than I was expecting. Obviously, some people came and they weren't that interested, but a lot of people were really moved by it and I suddenly felt that the music had an important role to play.’

At the beginning of each concert, whether in a school or in a prison (she is keen to point out the obvious differences between the two settings…), Hammond always introduces the repertoire with some background information about the composer or the music, but her Variations concerts will also introduce some simple musical analysis to her audiences.

‘In a variation, you obviously have a theme which is then repeated many times. Although there's a great deal of change in a piece, there's always that thread to hold on to and it's a nice way of getting audiences interested in a piece when they might not be familiar with the style.

‘Normally I would tell a biographical story about the composer and try to find something that was relevant to that audience, but this is the first time I've tried to do something that's analytical. I did a dry run – before lockdown I did a similar variations-based programme in one of the prisons and I was surprised by how well it worked. You wouldn't initially think that musical analysis, although it's on a very simple level, would be something that audiences who haven't encountered a great deal of classical music would be interested in.’

Fostering pride

Hammond always starts off with Mozart's ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ variations: ‘It's lovely to watch people's faces when you play a variation and they can hear that the theme is in there but the mood has changed completely and Mozart is playing around with different emotions.’ In the dry run, she also tried some of the Karol Szymanowski from the disc and introduced a few biographical details.

‘With the variations, you've got a very clear analytical hook to bring people in, and then you can add all these other elements around it.’

The main thing Hammond has noticed in her primary school concerts is the sense of pride felt by the children in the music that they have learnt, played, or listened to. ‘They're very keen to engage and to tell you that they sing or play this instrument, or that they like listening to this style of music. Their reactions are always very open.’

Even when introducing children to ‘extreme’ atonal music with ‘not much to latch on to’, such as ‘Toccata’ by Korean composer Unsuk Chin, Hammond says that ‘kids are completely on it’, expressing both enthusiasm and pride. ‘It's been really interesting to see – I think if you foster that early on, it can last through teenage years when things become a bit more complicated.’

Emotional power

In the prisons, Hammond says that her music serves as both a form of ‘respite’ from prisoners’ normal everyday experience, and as a way into exploring classical music in their own time because they've realised its emotional potential. ‘I think that's the key point – it's the emotional content of this music. In prisons, I usually try to find stories or choose repertoire where the composers have faced adversity. With some, it's mental health, which was a big thing for many composers, and that ties in with a lot of the issues experienced by many of the prisoners.’

On one occasion, Hammond told the prisoners about Schubert's syphilis before playing the Impromptu: ‘It's not something I would ever mention in my normal recitals, but just being able to talk about the stigma associated with the disease and the strain he was under, not being able to share this with anyone because it was so taboo. That suddenly caught the audience's attention and was really powerful to see.’

Playing the Schubert in a women's prison, Hammond made the split decision to tell her audience that she'd learnt the piece while her mother was dying of breast cancer, so she had always associated it with her and played it at her funeral. ‘Suddenly there was a shift in the atmosphere, and they were on my side and supporting me. I'm generally quite a private person and it's taken me a long time to bring any of my personal life into my professional performance, but I think it's an important thing to do as an artist or a musician.’

After another concert in a women's prison, Hammond received an email from her contact there telling her that one of the prisoners had been doing drug rehabilitation work and had felt very numb for a long time. However, the music had brought back a flood of emotions: ‘Obviously, that was good, but could have also been very difficult for her. But just to hear that music can have that kind of emotional power is really encouraging.’

Not just a luxury

While this brilliant work cannot continue in person until Hammond is able to visit schools and prisons again, we speak about what music provision in a post-Covid world could look like. ‘I think it's clear that the government doesn't value the benefits of music in terms of general cognitive development, social cohesion, and the resources it can give children throughout their lives.

‘There's been a lot of discussion about that recently. I hope some of it will stick and we can make access to this kind of music more equitable, because it's becoming less and less so. The idea that music is somehow a luxury and an entertainment is deeply flawed. To say that is to ignore completely all the other aspects that make it such a vibrant and rich tradition that can complement every other aspect of our lives.’

Design by Sveta Yavorsky

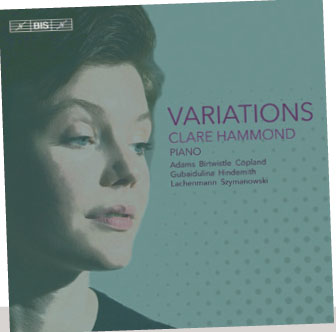

Clare Hammond's new disc of 20th-and 21st-century variations is out on 5 March 2021 on the BIS label.