Getting in the mix: becoming a studio assistant

Amrit Virdi

Monday, January 1, 2024

Former music tech student Tom Coath is finding his way in the recording industry at British Grove Studios. MT's Amrit Virdi meets him to find out more.

P. J. Gibbons

Music is a varied subject which can open doors to many careers. Numerous specialist courses have emerged in recent years, particularly when it comes to music tech and vocational pathways. One of the more established courses at university – specialising in sound recording and combining science and music – is the Tonmeister course at the University of Surrey.

Tom Coath, 24, is one of its graduates. While taking a few days' break from the madness of the music industry, he spoke with me from his family home in Norfolk about his career choice and working at London's prestigious British Grove Studios (owned by Mark Knopfler).

‘It's my mum's birthday so I thought I'd pay her a visit’, explains Coath from his rural childhood surroundings, a world away from busy London. ‘Day to day, my job is quite busy, but it really depends on what session is booked in. Usually, we set up the live room with microphones and chairs for the musicians, then the control room with wiring, electronics and files for the recording on the computer, all ready. Sometimes this means staying up late the night before and going into every film cue, where there's video, or putting in our templates and doing a ‘scratch’ test. So, typically, we've done a day's work before the recording day starts.

‘My role on the recording day is running Pro Tools, by pressing record and stopping when we do quick edits, and making sure the musicians have got the right elements (sound or parts) in their individual headphones. Or I'll be taking notes, and making sure that the team has teas and coffees when needed!’

From Robin Hood to the deep end

‘There's no real way that you can learn how a session runs, or what's important to do, without being in the room and seeing what's happening. It's amazing that as soon as you suddenly have to use equipment, and you've got no choice but to use it, you pick it up quickly’, says Coath, who admitted having ‘plunged in the deep end’ with work after graduating and starting his role at British Grove, working with Dire Straits guitarist Mark Knopfler among others.

Though only a few years into his career, Coath says a highlight so far was working as an assistant orchestral engineer for Peter Gabriel's new album – an artist who he appreciated working with, particularly as it was someone his grandma was aware of! ‘This was the second time I'd ever recorded, and I had so many horrible little technical things that happened in the days leading up to it; but it was one of those where the actual recording just went great’, he reminisces.

‘I actually wanted to be Robin Hood when I was seven’, he laughs, when asked if this was always the plan. Growing up playing bass, guitar, piano and dabbling in indie-rock bands while also songwriting, Coath experimented with DAWs in an effort to bring to life the multi-instrumental tracks that he was making. This led him to take A Level Music Technology and then the Music and Sound Recording (Tonmeister) degree at Surrey.

Tonmeister training

The four-year Tonmeister course was the first of its kind in the UK. It can be completed as a BSc or BMus, depending on the scientific or musical emphasis of chosen modules. The options available made the course stand out to Coath. He describes it as ‘quite a tough course, in terms of the amount of science and technical know-how covered’, but praises it for providing ‘a comprehensive background’.

Recording engineer and producer Ken Blair has come full circle, joining the Tonmeister undergraduate programme in 1984 and now teaching the course's young hopefuls. Spending his third-year placement working at George Martin's AIR Montserrat Studios, Blair experienced what the course had to offer, recalling how former peers have since gone into a wide range of industries, including film and gaming. In 1989 Blair set up his own UK-based location sound recording company, BMP, which specialises in classical, jazz and acoustic music.

‘The course's value for career progression’, said Blair, ‘is down to a number of key factors, including the quality of the teaching (from academics and professional practitioners), the calibre of students, the excellent facilities and the combination of academic study with practical experience. The standard of work expected from and achieved by students in coursework is very high, but the course provides a combination of deep theoretical knowledge and lots of practical and industry experience.

‘It forms well-rounded engineers because much of what is taught in the classroom regarding audio and video is solid theory and principles. For example, when it comes to mixing consoles, students aren't taught how a specific model of mixing-desk works, but rather the principle of mixing-desk design and operations. This means that no matter what desk they come to, they should have a good idea of what to expect and how to find their way around it.’

Opportunity

Coath acknowledges that being a Tonmeister undergrad offered him the opportunity to complete an internship (unpaid) at the coveted Eastcote Studios, where he says his tasks included ‘running around and plugging things in’. Though this placement wasn't easy to find or self-fund, he praises the placement scheme for giving him the opportunity to build the skills needed for his current role and to network.

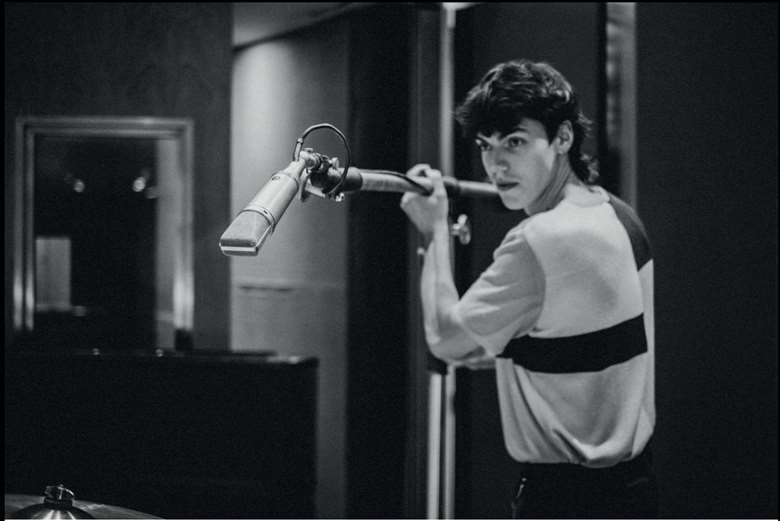

‘Doing an internship can be a very effective way to get your foot in the door of an industry. I have friends who were offered full-time jobs by their employer after their internship finished, and lots more, like myself, were able to use the experience and contacts they'd made to secure work in the industry. So much work in the recording industry comes through contacts and word of mouth. The majority of the placement students on my course did paid internships. However, my internship was unpaid. Although I gained a huge amount of experience and new skills, I would warn others to be cautious of embarking on an unpaid role.’ Students on the Tonmeister course have access to a range of industry-standard equipment

Students on the Tonmeister course have access to a range of industry-standard equipment

University of Surrey / Grant Pritchard

Taking the long view

Those working in this sector have long criticised the treatment of music within the school curriculum, despite its value to the economy. Figures from the Joint Council for Qualifications reveal that A Level Music entries in the UK in 2023 fell by 7% from the previous year, at a time of growth in digital media, video and gaming sectors. That said, intakes of students for vocational music courses have risen: MT reported in April this year that 83 students in England obtained a vocational qualification when this was introduced in 1994, but close to 40,000 students now study for a ‘VQ’ across KS4 and 5. There's some excitement around the upcoming launch (Sept. 2024) of the media, broadcast and production T Level, a practical, experience-based form of study, but this doesn't cover music.

Coath describes the Tonmeister course as being the best part of his education, saying that the mentality of using your ears and understanding what you're doing, with knowledge of philosophy and technique, is the best way to learn. But he calls for there to be more encouragement of taking music-based courses and qualifications in the education system, and for these to be more engaging.

‘I remember how the early years (before GCSE) were really collaborative, whereas heading into GCSE and beyond, it becomes a lot more about the syllabus for the exam and facts. I really enjoyed my A Level, but the focus of it was to get everyone to pass, and it was very broad, with a lot of content. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it becomes less fun and you lose a bit of musical freedom. The most rewarding experiences I've got from music have always been about collaboration, not an exam or a performance piece’, explained Coath.

‘But for anyone in education wanting to go into sound engineering, my advice would be to record everything you possibly can for free or for little reward, so you get invaluable experience of working with musicians and recording them. Obviously, it's a hobby [to begin with], and I appreciate it's not the most inclusive due to cost. But you can get by: I spent all of high school and sixth form using beginner Focusrite, with a £60 mic. It sounded rubbish, but it was a good start!’