Maurice Porter: the embouchure dentist

Chris Walters

Friday, December 1, 2023

Chris Walters explores the life and work of Maurice Porter, a pioneering dentist and amateur clarinettist who helped musicians overcome embouchure issues.

British Dental Association

Embouchure, meaning the position and shape of the mouth when playing a wind instrument, is a vital part of woodwind and brass technique. Lip and tongue position are important in this, but so too is mouth health. This includes dentition: the formation and condition of the teeth.

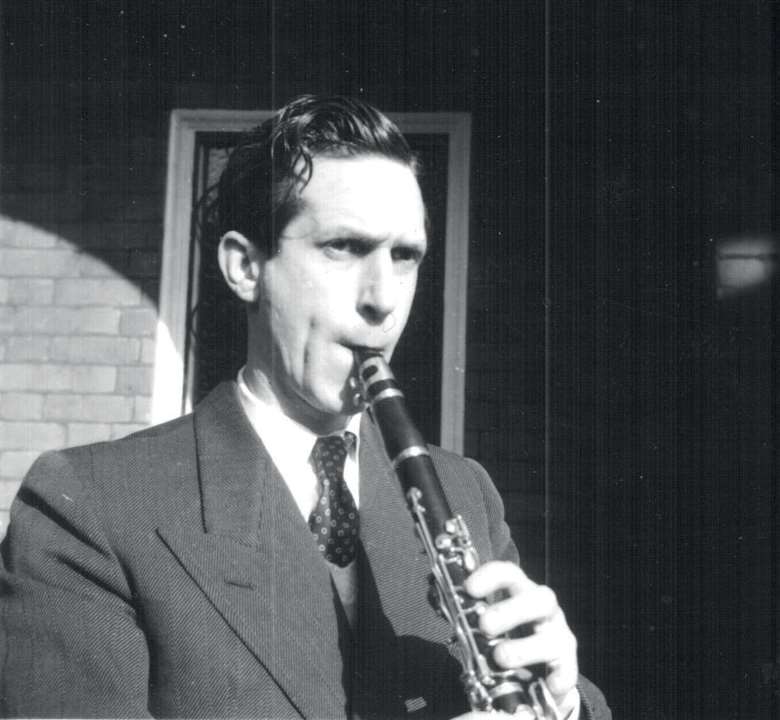

Understandably, many dentists are not up to speed on the specific dentistry issues that can arise for wind and brass players. What specialist knowledge there is stems from the work of Maurice Porter, a pioneering dentist who essentially developed a new field of dentistry to help wind and brass players resolve physical problems with their embouchures.

Inside knowledge

As an amateur clarinettist, Porter understood how a player's dentition, lip and facial structure related to the sound that they created. Crucially, he also came to understand the importance of these factors in relation to a musician's overall wellbeing.

The embouchure problems he treated were naturally occurring as well as caused by injury or inappropriate dental treatment. He advised on suitable treatments to improve players’ comfort and performance, enabling musicians with poor dentition and facial injuries to perform again with confidence.

Porter was born in 1909 into a poor immigrant family in the East End of London. At the outbreak of the Second World War, he volunteered for the British Dental Corps and was posted to Palestine. He was later promoted to officer in charge of the dental department of the Middle East Military Hospital – and so began a remarkable career.

Remaining in Palestine until the end of the war, he treated soldiers with serious facial injuries. Among them was a severely injured army bugler, who pleaded with Porter to restore his facial musculature and dentition so that he could play the bugle again.

‘This episode greatly influenced my father personally’, recalls Porter's son Robin. ‘As an accomplished amateur wind musician, he decided to specialise in the dental problems of wind and brass musicians and their treatment.’

By the 1950s, Porter had become an authority on embouchure, giving lectures to dentists and musicians in the UK and US. He also had papers published in the British Dental Journal about the problems encountered by wind and brass musicians, a subject that had largely been overlooked until that time, and in subsequent years wrote a book called The Embouchure (Boosey & Hawkes, 1967).

Exhibition

Much of the content of his writings and lectures, along with various accompanying photos and sketches, was featured in an exhibition at the British Dental Association (BDA) earlier this year. The exhibition also included his correspondence with famous musicians, dentists and music teachers from across the globe.

Also on display at the exhibition were performance dentures and other temporary devices specifically made to be worn when playing, and 3D models and detailed drawings of the facial muscles used in playing different instruments.

The exhibition website remains available to view as a permanent reference for continued study in this field. It includes video interviews with contemporary players and dentists, other film clips and biographical material. It also gives access to Porter's published BDA papers.

‘Maurice Porter's dedication and passion for supporting musicians was incredible’, says BDA Museum head, Rachel Bairsto. ‘We are delighted to be able to share his story and celebrate his pioneering work, which helped so many musicians play to their full potential.’

Anatomy of a clarinet embouchure. Courtesy British Dental Association.

Anatomy of a clarinet embouchure. Courtesy British Dental Association.

Dentistry advice for musicians

The exhibition website is a valuable source of advice for wind and brass players experiencing problems. It lists a number of organisations that can support musicians, of which the most relevant in terms of dentistry is probably the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine (BAPAM). It also discusses relevant areas like oral health, dental problems, lip shields and performance dentures.

The Musicians' Union (MU), in partnership with BAPAM, recently hosted a webinar on mouth health for musicians, which is still available to MU members on the MU website. Topics discussed in the webinar include traumatic ulcers, dry or cracked lips, denture retention, oral health (what not to do), postural influences on oral health (jaw, jaw muscles and embouchure), breathing mechanics and focal dystonia.

With most long-term healthcare, managing and working with imperfections is often a more realistic aspiration than hoping all problems can be prevented or fully eradicated. The story of Porter's career is arguably one of supporting musicians through challenges that can't always be resolved, such as unusual dentition, and those that can't be predicted, like unexpected injury. Porter showed that musicians can often overcome what previously would have been career-ending embouchure problems – a legacy to be proud of.