Demystifying Composition Column: Harmonic structure

Melanie Spanswick

Wednesday, April 1, 2020

Having explored creating a piece from just a few pitches and rhythmic patterns in previous columns, this month Melanie Spanswick looks at using harmony as a form of structure.

Melody most definitely plays an important role in any piece of music. Even if there isn't a concrete melodic line, there will usually be some evidence of melodic motifs or fragments. Often students will write their own melodies; they will tinker at the piano and piece together a tune. But then comes the tricky part: harnessing their melody to a solid harmonic structure, and elongating that structure – turning it into a piece. How will they go about adding a suitable harmonic pattern that complements the melody they've written and provides a fitting accompaniment?

One way of alleviating this issue is to concentrate on creating the harmonic structure before any melody is even attempted. This may seem back to front, but it can be surprisingly simple to create a harmonic pattern that will be effective, easily proffer a tune, and of sufficient interest to form the basis of a piece.

Start with manuscript paper and a pencil (or digital equivalent). This exercise relies on ‘hearing’ chord progressions, so if students can't play the piano or an instrument, it's best to help them to work through the exercise.

We are going to create a four-bar phrase from a series of chords. Choose your key; you may prefer to start with C major for simplicity.

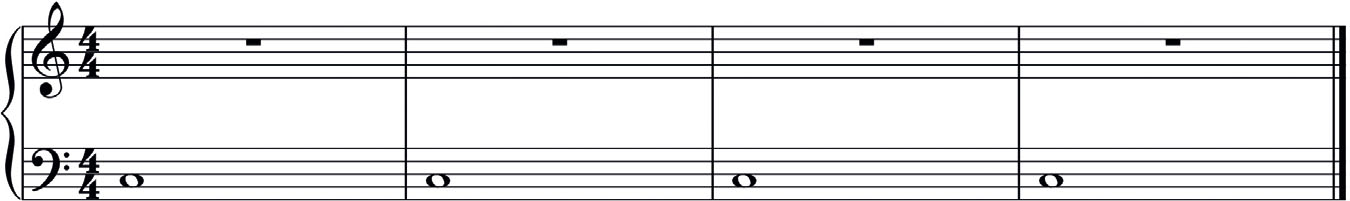

The tonic (key note) will form the basis for our progression. I am going to choose C major/minor (it can be a good idea to use a key's major and minor tonality for this exercise to make available a wider range of harmonic colours). My tonic is therefore C. Write a time signature of 4/4 and place the tonic as a semibreve at the bottom of the chord in each of the four bars (Fig 1).

Fig 1

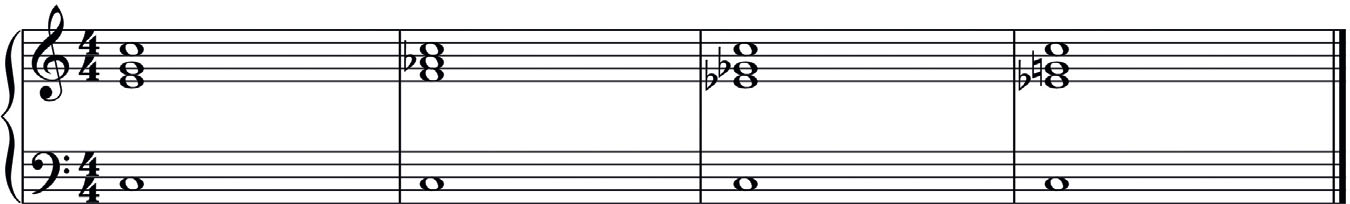

On top of the Cs you will need a series of four chords (one per bar). C major will be your first chord, and this will be followed by two further chords, probably each with a slight chromatic twist, ending with another C major (or minor, as I have done in Fig 2).

Fig 2

Locating the correct chords is trial and error. Our students are not relying on ‘knowing’ particular chord progressions because they might not understand these yet. I find that it helps to play and listen to each chord slowly, one after the other, to see how they work together. You may have to do this for your students at first. Eventually they will find a combination that works well just by playing notes together (with the tonic in the bass), ‘hearing’ if they work well one after another.

Harmonies can be spread between each hand or clef if preferred, but I find it easier to hear the chords in the treble clef with just the one note in the bass. For those who aren't secure with note reading, or prefer to write in shorthand, the notes of each chord might be written more simply as letters (this is a good idea for speed).

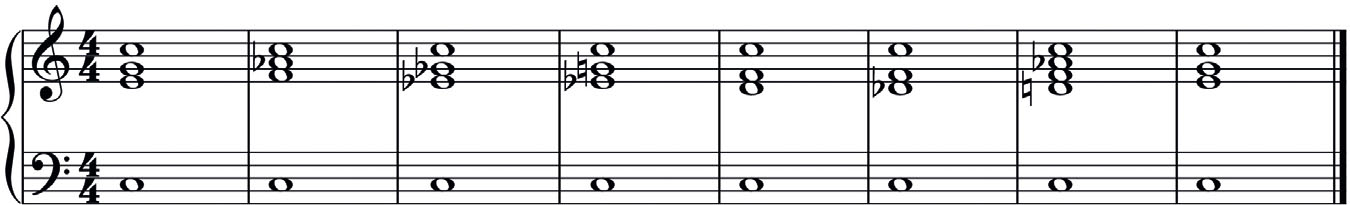

The four-bar phrase now needs to become eight bars. You could keep to a four-bar phrase, but adding another four makes for a more compelling phrase and for greater possible development. Add another four bars with the tonic at the bottom of the harmony; you could add the tonic at the top of the chord too. The last bar will be a C major chord (therefore ending on the tonic), and the previous three chords will, again, need to be a progression with which your student feels happy (Fig 3, for example).

Fig 3

I have deliberately selected fairly diatonic chords that are centred on using flats, and that will work when played in succession. Students can have fun devising their own chordal system here.

Now that we have our eight-bar phrase, we're ready to begin the compositional process by using it creatively to construct a piece. This will be continued in next month's article.