Tech column: music-tech-as-performance for GCSE Music

Rob Abba

Friday, December 1, 2023

Rob Abba, a teacher at Loughborough Schools Music, uncovers the untapped exam potential for less traditional 'performers'.

Adobe Stock / evgenydrablenkov

While performing using technology has been an option for some years, it has arguably become a lot more interesting in the most recent iterations of GCSE Music specifications. However, it is under-utilised by learners and teachers as an alternative method for those who are perhaps not the best performers in the traditional (instrumental) sense.

One reason why it might be under-utilised is that it is not well understood. This is not helped by the wildly different interpretations by the various exam boards. I have summarised below the exam board approaches, in order of increasing interest:

All of these requirements are for the solo performance. Requirements for an ensemble performance are generally similar but sometimes involve a third-party playing on the performance.

When using MIDI sequencing techniques, the learner must be able to create a sense of performance, i.e. an accurate sense of how a good musician would play the music. This is what separates it from merely a note-inputting exercise. This also demonstrates the music-tech skills of the learner as well as their musicality. Below are examples of how this is achieved.

Velocity editing

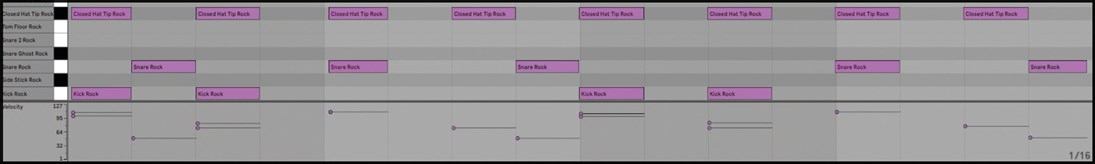

Velocity is the volume of an individual MIDI note. Learners can create shape and ‘micro dynamics’ in melodic phrases by editing this parameter. Notated dynamics and accents can also be implemented through velocity. Another good use of velocity editing is to create a greater sense of groove in a drum pattern. Figure 1 is the ‘before and after’ for a drum groove edit. Hi-hat off-beats and snare ghost notes have been lowered, and the kicks and snares on the beat increased.

Figure 1: Velocity editing - before and after

Figure 1: Velocity editing - before and after

- Edexcel. Learners perform using, for example, electric guitar or synthesiser, perhaps with live use of effects and processes. They are assessed in the same way as a traditional instrument. (This is essentially pointless!)

- Eduqas/WJEC. Students sequence a backing-track and then perform a solo line over the top. This has to be performed live and in one take. The live element and backing-track are then assessed holistically.

- OCR. Here, there's a choice: 1) A multi-tracked recording where the learner performs at least one part. This is assessed in the same way as a traditional performance. There is no credit for doing the recordings. (Longwinded and somewhat pointless.); or 2) A sequenced recording (MIDI) where the learner programs all parts. There must be some element of live control to create a performance or ‘happening’. This could be playing a part live, controlling/effecting a part live, or triggering the playback of various parts live. (This is much more interesting!)

- AQA. A complete production of a pre-existing piece of music using sequencing and/or multi-track recording techniques. It must contain at least three tracks, and one track must be recorded in real time. However, unlike OCR, this is not a ‘happening’; it is truly a studio production, not intended to be consumed live or with an audience. The part played-in live can be recorded in multiple takes and edited afterwards, e.g. using quantisation.

Swing/groove

This applies mostly to drum parts but can be applied across all instruments. A small amount of swing (e.g. 10%) can really add life to a performance that sounds over-quantised. Many DAWs can also apply groove templates to the MIDI part. In Figure 2 you can see how the MIDI notes have been moved slightly (seen most clearly on beat 2) by the groove template to give a more natural, human feel.

Figure 2: Adding swing/groove

Figure 2: Adding swing/groove

Pitchbend and modulation

Many vocal and instrumental performances include small and gradual variations in pitch rather than the instant switching of pitch that we generally associate with MIDI. The pitchbend wheel, usually found on the left of the keyboard, can create a much greater sense of expression, if used tastefully. Some software instrument sounds have a natural vibrato built in, but if not, encourage your learners to experiment turning up the modulation wheel during long notes.

Note length

This is not about accurate rhythm; it's more about changing the length of the note to a more musical interpretation, or indeed to match a notated articulation. This could also be cutting notes slightly short where the player would take a breath.

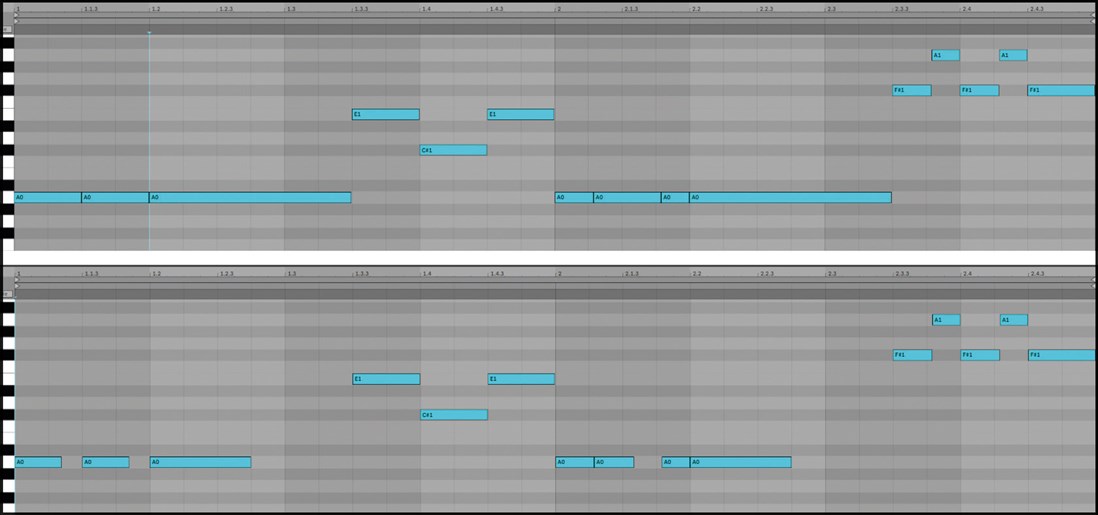

Figure 3 illustrates the bass line for ‘Three Little Birds’ by Bob Marley. The first screen shows the bass as it would be notated in a score, i.e. input with full note-values. However, it's possible to arrive at a more musical version using shorter note lengths, as in the second screen. Indeed, when comparing the original recording, this is much more accurate.

Figure 3: Adjusting note lengths

Figure 3: Adjusting note lengths

Tempo automation

Some pieces of music have tempo changes – some obvious, some more subtle. There may be a notated rallentando and fermata to deal with. Consider how ‘Happy Birthday’ is usually performed, and how a metronomic rendition would sound very odd. Recreating an authentic-sounding version in MIDI – while maintaining the notes ‘on the grid’ – requires a lot of tempo automation. Thankfully, most adjustments in well-known pieces are more subtle than this, but keep your learners aware of the possibilities.

Final recommendations

Time is a big factor in the success (or otherwise) of performing with technology. Most centres’ GCSE Music schemes of work don't allow much class time for performing, as it is usually expected that the learners work on this at home and with their instrumental teacher. Recreating two pieces of music in a DAW is a time-consuming process. Consider offering an extracurricular music-technology club, optional for fledgling music technologists in earlier years but compulsory for GCSE students taking this path. Those of you lucky enough to have a technician could draw upon their time and expertise to staff some of the sessions.

I would also encourage gaining a library of appropriate pieces that you know can be recreated effectively with these techniques. Have the scores ready to give to the learners, and also send off to the examiner!

Finally, make sure that you have, yourself, re-created a whole piece of music in MIDI. See how it feels, where the pitfalls are, how to create a convincing drum groove, and how to realise notated articulations. This experience is how you will best guide your learners.

Further Reading: