Tech column: using AI in the music classroom (part 2)

Tim Hallas

Monday, January 1, 2024

In the second part of his series on artificial intelligence, tech expert Tim Hallas explores its music-making possibilities.

Adobe Stock / Metro Hopper

In my previous article on the use of artificial intelligence in music education, I reflected on the ways that students and teachers can use large language models (LLMs) in lessons. This included students learning and developing skills through reviewing AI-generated essay plans, and teachers using AI to write emails to parents.

But AI is so much bigger than ChatGPT and other LLMs. AI and machine-learning have been around a surprisingly long time, and we use them daily without even realising. The automatic facial recognition in the photos apps on our phones is AI; Siri and Alexa use AI; and even autocorrect and grammar-checkers use AI. Music creation and production are no exception – and this article will look at a few of the different uses.

Composition

I recently went to the excellent Turn It Up exhibition at the Science Museum, about the power of music. With a significant section on AI and generative music, this included an exercise in which the listener had to guess whether pieces of music had been generated by a human or machine. And, I'll be honest, I got them wrong. It was very difficult, which, as someone who trained as a composer, I found most disheartening.

However, the pieces were all of ‘a style’. They were all electronic music in origin and heavily programmed. Therefore, in preparing for this article, I began to dive much deeper into the world of AI music generation. The main AI-based music software seems to be largely in two categories: generative music based on meta tags that create generic library music, and AI-based musical idea generators, which are little more complicated.

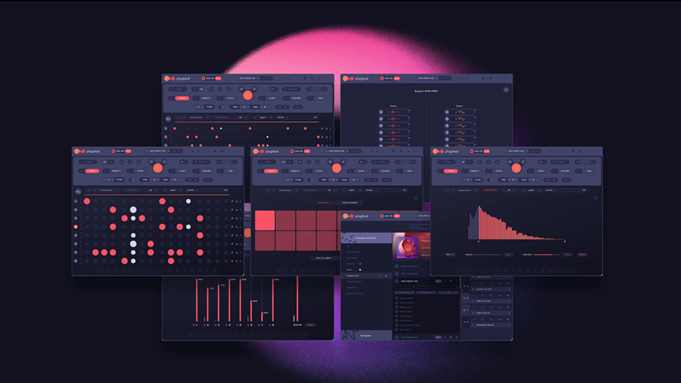

Playbeat analyses your music and suggests ideas

Playbeat analyses your music and suggests ideas

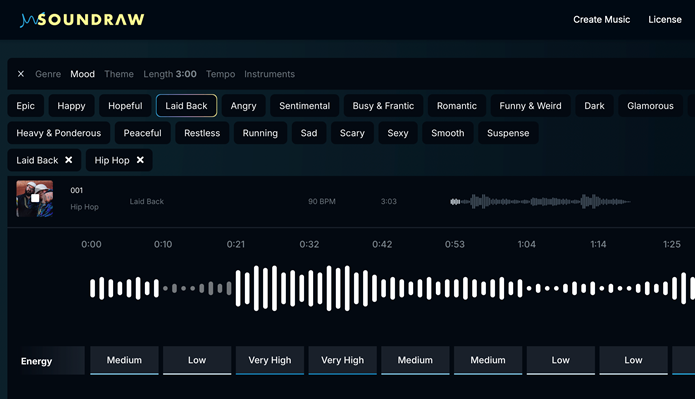

Library music

The first of these categories simply generates music based on a few keywords and then assembles assorted loops to create some rather generic-sounding music that works as background noise. These products are aimed at people who need cheap library music that is instantaneous and forgettable. But it is still an interesting experience to show this to students, so they can understand how certain genres are created and critique their own compositional practice.

There are free versions of these products available, and many of the paid versions allow limited free use. Websites such as Soundraw allow you to listen to limitless combinations but charge once you try to download them. The quality of these is exceptionally high – if you don't pay too much attention. However, once you start listening closely you realise that it's all very musically simple and isn't actually that interesting to listen to. Soundraw generates library music based on keywords

Soundraw generates library music based on keywords

Music analysis and generation

The other common form of AI software (the more complex one) is used in conjunction with other music software such as a DAW. These use the AI to analyse the musical content of what has been created and suggest riffs, chords, harmonies and rhythms based on the analysis. This is a very different approach and allows composers and musicians to develop a wide range of music at a fast pace. This has particular relevance to student composers who might have a lovely melody but need the AI to develop the accompaniment or a drum part.

These platforms return me to the debate around the ethics of AI. If a student (or a professional composer, for that matter) uses this AI-based software to enhance and develop their work, at what point does it stop being the composer's work? If AI develops a significant amount of the work, then who owns the intellectual property and, if it makes money, the copyright? I don't know the answer to these, but at some point the music industry (and JCQ) is going to have to work this out! Playbeat analyses your music and suggests ideas

Playbeat analyses your music and suggests ideas

Voice generators

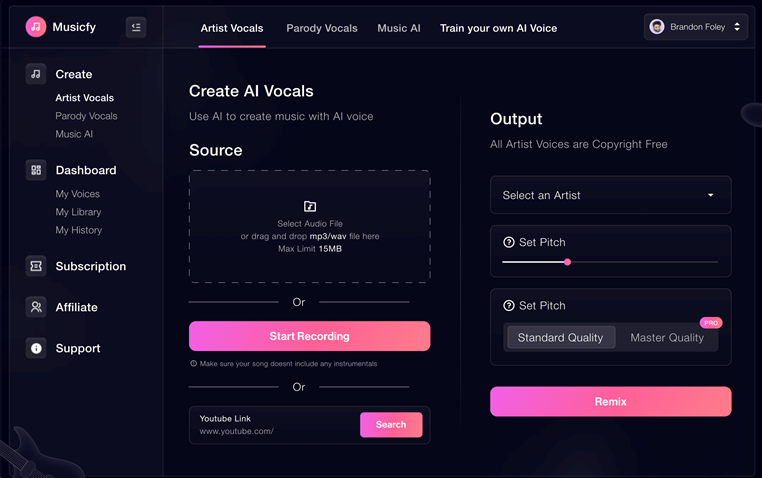

The products that seem to have hit the public consciousness in AI-based music are those that use AI to recreate the voices of famous singers. This is at best a novelty, and at worst an ethical and copyright nightmare. This was one of the key issues that actors raised in their recent strike in the US – if AI can recreate an actor's performance, how do we know that it won't?

The examples I've heard (Ed Sheeran singing Adele, anyone?) are very good and sound impressive. However, the versions I've experimented with are significantly of lower quality – they sort of sound like the person, but not really.

These platforms are of interest to students for amusement, but probably aren't really going to have much relevance on composition or performance tasks in the music classroom.

However, thinking much further ahead, voice technology is improving. I recently saw a video of a robot singing a song that it had written using machine learning. It had been fed thousands of songs and extrapolated both music and lyrics to create a song and then used voice technology to perform it – and it's very clever (I think it sounds a bit like The Divine Comedy). The robot, Shimon, can sing and perform its own composition with other non-robot musicians – watch on YouTube. Musicfy replaces vocals with AI voices

Musicfy replaces vocals with AI voices

Mixing

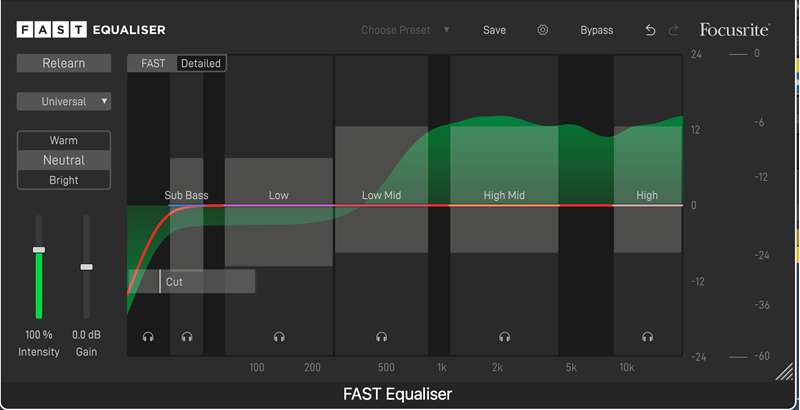

AI does have other uses in music, though, and these can be found in the supporting tools that producers use to mix and master their recordings. AI is now increasingly being used in effects and processors. My first experiences of these were with the Focusrite FAST processors that use AI to analyse audio and provide suitable settings based on that specific audio. One thing that I always tell my students is that plugin presets are largely useless because the preset doesn't know how their audio sounds. However, the FAST plugins do know how the audio sounds and, based on machine learning from countless other analyses, can provide meaningful presets and settings for a range of effects. FAST EQ analyses the incoming audio and applies an AI generated EQ curve

FAST EQ analyses the incoming audio and applies an AI generated EQ curve

Mastering

The use of AI to master audio has been around for some time, but it is now becoming more prevalent. The big name in this world is Landr, and some mastering houses are now specifying that their work will be carried out by humans – ‘we're better than Landr’ is not an uncommon phrase on websites.

However, professional mastering for student work is usually out of the question, and the fact that Logic now includes an AI mastering plugin is a clever addition. I'll be teaching my students how to use it, critique the results, adjust its settings and compare it to their own efforts.

Vocal separation

The last key tool that a lot of musicians are using AI for is removing vocals from commercial recordings. This is to create instrumentals for use as backing-tracks or to create a capellas for use in remixes and so forth.

This is something I've been using with my students since I first discovered LALAL.AI, which we've been using to isolate parts in tracks (to learn them), for sampling or for creating guide-tracks. The most common use is for vocals – but this technology can, theoretically, be used on any part if the machine can learn how it sounds. This is essentially the same process that was used on The Beatles: Get Back film and the ‘new’ Beatles song, ‘Now and Then’.

Final thoughts

The idea that AI is new is a misnomer: it's been around for some time, but it has only recently reached the public consciousness. The different ways in which it can be used in music raise creative and ethical questions; but, when used appropriately, can open up many more musical doors that would otherwise be shut, particularly for those with additional needs.

As with the worries about plagiarism with ChatGPT and similar, the use of AI in music can be used to create limitless muzak; but, as a tool, it potentially opens up a much wider set of skills to musicians.