Communicating through song: language acquisition in Early Years

Sue Nicholls

Thursday, February 1, 2024

Early Years/Primary consultant and author Sue Nicholls explores how to develop language through singing.

Adobe Stock/Nina L/peopleimages.com

In my many conversations with Early Years practitioners, one topic always arises: the significant number of children between the ages of three and five exhibiting a worrying lack of language and communication skills.

The Early Intervention Foundation, an independent charity focused on promoting and enabling an evidence-based approach to early intervention, summarises succinctly the importance of a strong start: ‘Early language acquisition impacts on all aspects of young children’s non-physical development. It contributes to their ability to manage emotions and communicate feelings, to establish and maintain relationships, to think symbolically, and to learn to read and write. While the majority of young children acquire language effortlessly, a significant minority do not. We believe the fundamental link between language and other social, emotional and learning outcomes makes early language development a primary indicator of child wellbeing’.

Research tells us that when young children have poor oral communication skills, the knock-on effect can impact their progress in school and beyond.

Many factors, including those rooted in complex socioeconomic trends, contribute to limited language acquisition. Here are a few examples reflecting recent changes in societal routines and behaviours:

- More isolated babyhood of today’s Reception children resulting from the Covid pandemic

- Increased dependence on television or screens to occupy children

- A lack of stimulating conversation in the home, from family members ‘plugged’ into phones/screens

- The dwindling practice of reading stories to young children at bedtime.

Music’s kinship with language

Unsurprisingly, music and language have strong structural commonalities, as evidenced in a recent review of literature about the relationship between music and language: ‘… music plays a critical role in language development in early life. Our findings revealed that musical properties, such as rhythm and melody, could affect language acquisition in semantic processing and grammar, including syntactic aspects and phonological awareness. Overall, the results of the current review shed further light on the complex mechanisms involving the music-language link, highlighting that music plays a central role in the comprehension of language development from the early stages of life.’ (Pino, M. et al, 2023)

This identified shared ‘processing’ is a strong argument for how music, particularly singing, supports the development of language and presents us with opportunities to improve children’s impaired communication.

How singing supports language acquisition

Lyrics and ‘stickability’

Teachers have long recognised that sung lyrics ‘stick’; it’s as if melodies pin the words to the memory. So, a song learned decades before can be recalled word for word, without effort. This ‘stickability’ and ‘lyrics memory’ is something that we can exploit in the choice of songs that we introduce in our Early Years settings.

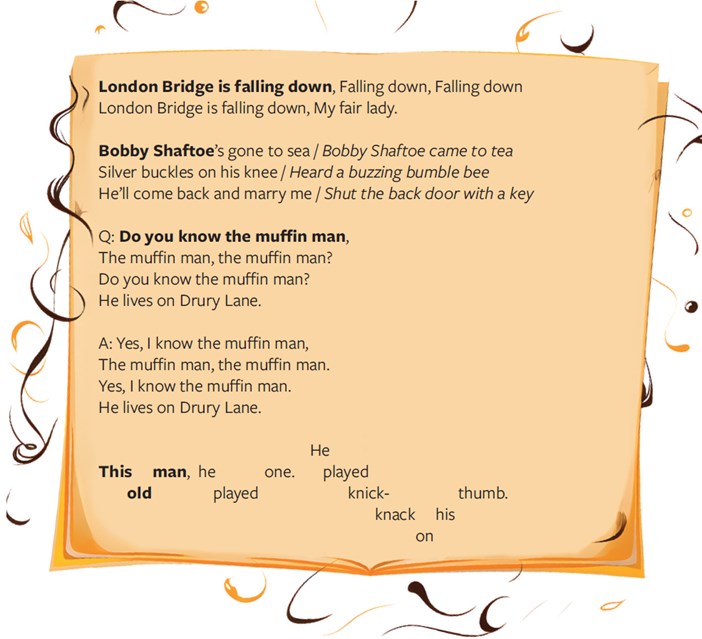

Another key advantage that songs have over speech is the convention of repeated lyrics, which is accepted without question. This is true of some of our most cherished nursery songs, such as ‘London Bridge is falling down’, presented on the opposite page (see box). The repetition here sounds charming and natural when sung but would be regarded as extremely odd in spoken dialogue. It reinforces grammatical structures, parts of speech (e.g. present participles) and vocabulary. You can apply the same repetition to made-up action or transition songs, as in ‘We can put our toys away, toys away, toys away/We can put our toys away – Let’s get started!’

Rhyme

Song lyrics usually have rhyming lines – a convention that can be a real headache for songwriters. Apparently, A.J. Lerner agonised over his lyrics and spent hours seeking a stronger line than ‘Why all at once my heart took flight’ to rhyme with ‘I could have danced all night’ (from My Fair Lady).

Early Years song lyrics offer an opportunity for consolidating rhyming patterns, incorporating predictive rhyme games and experimenting with rhymed substitutions. This is true of ‘Bobby Shaftoe’, for example, which can be developed as in the example opposite.

Question and answer

The question-and-answer format also appears frequently in nursery songs. An example is ‘Do you know the muffin man’, which has the advantage of lending itself to being shared between group members too, while developing listening.

Such structures, when used as a scaffold, can prompt all kinds of creativity with newly-invented lyrics. This provides scope for new, original material and helps children recognise and differentiate different language constructions. This, again, can form part of everyday activity: (Q) Can you find the Lego box? (A) It’s somewhere in our room.

Song creation

Once you’ve become used to borrowing and adapting public-domain tunes, you’ll find yourself singing new songs spontaneously. It’s important, though, to keep to the original repetition ‘template’, to maximise the language learning potential. Children will copy your modelled songs and invent their own, too, and this burgeoning song creation should be encouraged.

Unaccompanied singing and pitching

Singing ‘live’ to children, and without backing-tracks, has great immediacy. It’s likely to elicit a positive response and develop better listening skills. According to Sally Goddard Blythe, director of the Institute for Neuro-Physiological Psychology: ‘Children’s response to live music is different from recorded music. Babies are particularly responsive when the music comes directly from the parent. Singing along with a parent is good for the development of reciprocal communication.’ (For ‘parent’, you could use the word ‘practitioner’ or ‘carer’ also.)

My advice is to learn your material and sing it from memory, never from a book or screen. You need to be alert to children’s reactions: Who’s attempting to sing with you? Who’s not singing but watching and listening intently? Who isn’t responding?

Singing in the right vocal range is also crucial. Many enthusiastic practitioners sing at a pitch that’s too low for young voices. A useful tip is to imagine the note on which you usually begin, then let your voice climb up five ‘pitch steps’ to a higher range that children can adopt.

Selecting your material

Short one-verse songs are ideal, as are one-verse songs with a single changeable word for extra verses. It probably goes without saying that you should avoid songs with tunes that leap around, with big jumps between notes. These are generally not conducive to best practice for developing singing.

Vocal experts favour two melodic features as essential components of Early Years singing. Firstly, ‘cuckoo notes’, which describe the relationship (or interval) between two notes that are quite close in pitch. Think of the opening of ‘This old man’ and its first six notes (‘This old man, he played one’). These are the ‘cuckoo notes’, and the interval in question (the minor third) is particularly recommended as an early building block. The best EY song collections will contain many examples with this interval.

The other age-appropriate feature is the use of ‘stepping’ or next-door notes, often a series of notes using the smallest pitch steps. Think of the next phrase of ‘This old man’: ‘He played knick-knack on his thumb’ is sung to seven notes that lie next door to each other (in pitch). When written out and presented graphically (see below), the song reveals how these features are baked-in.

Singing Circles

During lockdown, I created an EY eBook entitled Singing Circles, with 24 songs to promote language acquisition and social play, and which work alongside the specific characteristics of ‘scrunchies’ (large stretchy fabric rings,) lycra sheets and parachutes. I’ve always maintained that singing in a circle is the best arrangement for this age-group: it provides eye-contact for all participants, and allows those with linguistic, vocal or social needs to be positioned where they feel confident and where they can be engaged. Songs that use circular devices also provide opportunities for vocabulary involving direction and travel – in, out, front, back, inside, outside, turn, walk, skip, jump, and so forth.

The eBook – with recordings, scores and practitioners’ notes – is available free of charge and downloadable from the Music Teacher website by clicking here.

Links and references

- eif.org.uk

- sallygoddardblythe.co.uk

- Pino, M., Giancola, M. and D’Amico, S. (2023) ‘The Association between Music and Language’, Children

- Singing Circles eBook: download free