Book reviews: Music in Early Childhood

Jimmy Rotheram

Thursday, February 1, 2024

Jimmy Rotheram reviews Susan Young's ‘Music in Early Childhood: Exploring the Theories, Philosophies and Practices', published by Routledge.

While there will always be methodological purists, the vast majority of Early Years Practitioners (EYPs) I have encountered are pedagogical omnivores, keen to gobble up anything which aids the holistic development of children. For me, the best EYPs are able to switch modes – they may be using direct instruction and B.F. Skinner-style behaviourism to deliver group singing one minute, and the next guiding children through exploratory, organic child-led discovery of their own musical preferences. Thankfully, in her new book, Susan Young doesn't favour a narrow approach nor claim to provide ‘everything you need to know’. Instead, the book provides a broad overview of many of the movers and shakers in Early Years and some rare gems from lesser-known theorists.

As Young explains in her introduction: ‘A strong motive in writing this book was to bring to light the work of music educators whose work is less well known or has been forgotten. What is valuable is that these were practising teachers who wrote about their first-hand experiences, so they offer real-world descriptions of practice. There was a generation of music educators, notably from the 1950s onwards, who endeavoured to apply theories, mainly from psychology, in practice and their detailed attention to the processes of teaching and learning deserve, I think, to be better known.’

Young guides us through all this, offering a summary of each philosophy and its key principles, key texts for further reading, and examples of practical application in the classroom. Each approach is also given space for ‘comments and connections’. For example, Young shows how John Dewey’s holistic approach mirrors Émile Jaques-Dalcroze while rejecting aspects of Friedrich Froebel’s work for being ‘too vague’.

Structured survey

Part I looks at Skinner, behaviourism, imitation and reinforcement. It’s fair to say that this is the model of ‘knowledge-rich’ learning beloved by the Department for Education, and the prime methodology of many US and UK schools. Such teacher-led approaches are incredibly useful in making musical information stick and managing behaviour through routine. However, educators who recognise the need for a more expansive and holistic approach in EYFS will not want to stop there.

Part II explores how the ‘child-led’ ideas of Early Years generalists Froebel, Dewey, Maria Montessori and Susan Isaacs evolved and were applied to music education.

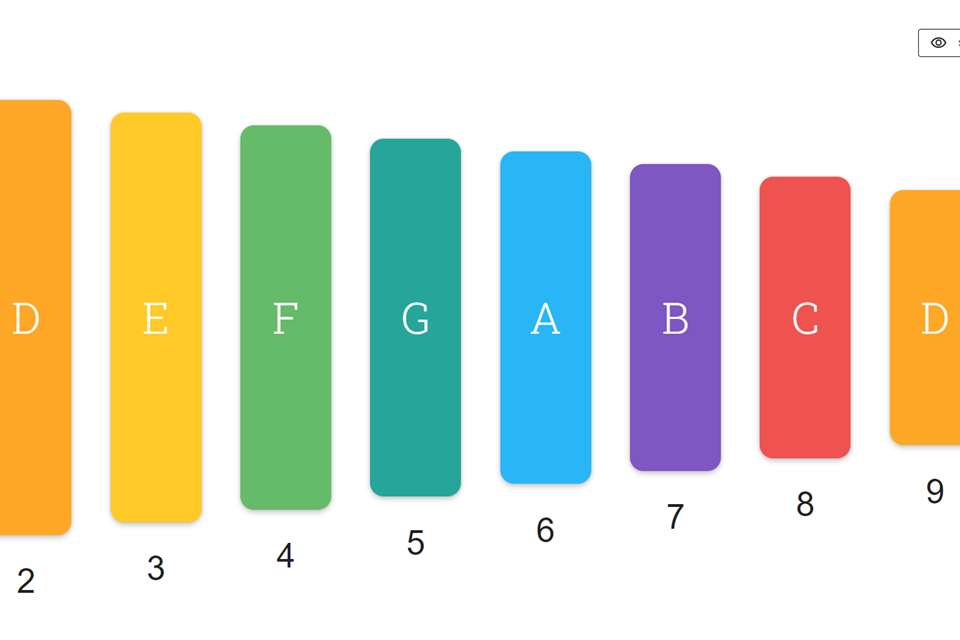

Part III presents us with a concise overview of the ‘Holy Trinity’ of childhood music education giants: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff and Dalcroze. It invites us to consider how their approaches connect and differ, and how adaptation can be beneficial but can also potentially mutate or dilute the original principles.

Part IV looks at how psychologists have influenced Early Years education since the 1960s through the prisms of another Trinity of men: Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky and Jerome Bruner. However, it also looks at the role that women such as Eunice Boardman played in building on and applying Bruner’s work.

Part V offers us a broad array of approaches which have influenced modern practice, drawing on ‘sociology, ethnomusicology … theories of learning through play and advances in infant psychology’.

Lifetime learning

The only criticism I could level at a book like Young’s is it can only hope to provide a very broad overview. At times, important issues such as decolonisation feel a little too broadly brushed. Moreover, unless it’s the size and weight of a breezeblock, such a book cannot hope to have the level of depth needed to start immediately applying any of the approaches with confidence in the classroom. Therefore, if you only have time to read one book about Early Years music education don’t make it this one. It requires CPD, research and investigation. Like learning a musical instrument, any of the approaches covered could be studied at greater depth for a lifetime, and many have societies devoted to just that, including Dalcroze UK, Orff UK, the Froebel Trust or the British Kodály Academy, from whom you can and should learn more.

However, for what Young calls the ‘pedagogical pluralist’, this book is an invaluable overview of a very balanced range of well-known educational approaches. It also celebrates women whose work risks being overshadowed, including Isaacs, Boardman and Frances Aronoff. I am confident in recommending this book to music specialists, Early Years generalists, school leaders and anybody wanting to learn more about this essential and often overlooked stage of musical development.

Postscript

The world of EYFS music is smaller than we would all like it to be, and as someone who has worked with thousands of practitioners, I do occasionally run into what could be perceived as conflicts of interest. In the spirit of openness, therefore, I declare that this book’s printed jacket carries the following endorsement from me:

‘Susan Young provides an incredibly broad overview of approaches to Early Years Education, from traditional, well-established music-centred “methods” and child-centred approaches to the fields of sociology, musicology and psychology. Young encourages us to think critically and practically about how we can apply such thinking in our own work today, and signposts many useful avenues of further development which will appeal to both newcomers and more experienced practitioners alike.’

I stand by these words, there was no remuneration involved, and I would certainly not recommend a book which I didn’t fully believe in.