Tech Reviews: Dorico 4

Dale Wills

Sunday, May 1, 2022

Dale Wills tests out Dorico 4 from Steinberg and tells us his thoughts.

A student recently approached me to ask for advice about potential film composition courses. Reviewing the potential list of available options set me thinking about the space between how composition is delivered in the commercial environment and how we go about teaching it. Does the way we deliver composition tuition at secondary and tertiary levels set students up for the realities of working as composers in the 21st century?

I was really excited to see a rescoped and reimagined Dorico 4 hit the shelves at the start of the year and was keen to see how this new version sits with my workflow. Prior to retraining as a teacher, I spent several years working in film and TV production. Having commissioned dozens of scores during this time, the thing that impressed me most was the turnaround time from brief to delivery. Modern commercial composers, whether they work electronically, acoustically, or most frequently, a hybrid of the two, can produce a score in a matter of days.

A new interface

Dorico hit the shelves in 2016, promising a user experience that matched the way people write music, rather than expecting us to adapt our workflow to the software. The latest version is available in four editions: Pro, Elements, SE and, iPad. Steinberg helpfully provides a detailed comparison chart for the four versions to help you decide which one meets your requirements.

Dorico produces beautiful printed scores with stability and reliability that are streets ahead of the competition, but I've never thought of a notation package as being the starting point for creation – I thought the act of slavishly dragging noteheads around a screen is antithetic to realising an idea. However, Dorico 4 aims to speed up the process. The new interface is more reminiscent of Steinberg's Cubase, with a lot of the boilerplate decisions made at this stage, such as time signature, key signature, instrumentation, and number of bars.

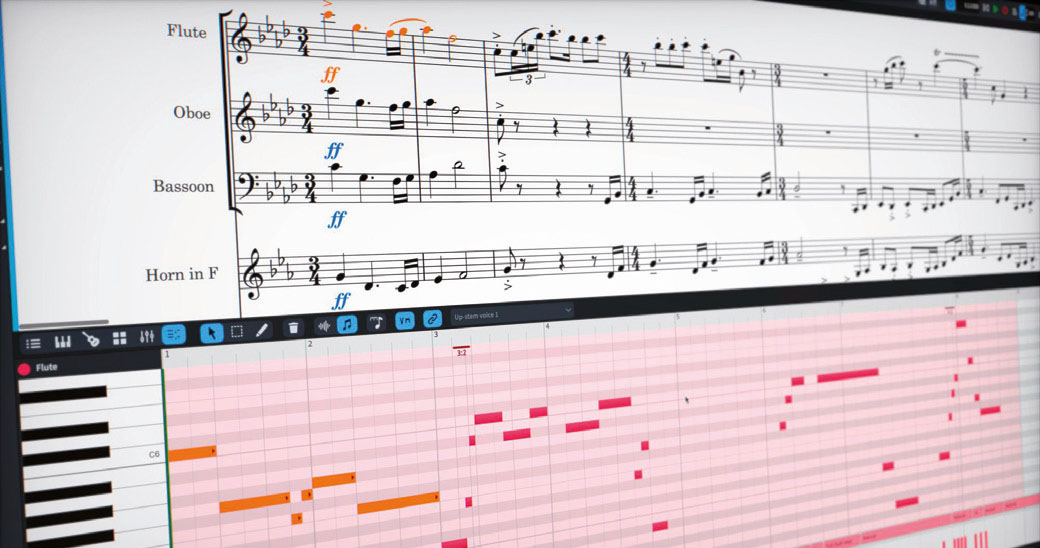

The ‘properties panel’ has become a newly designed ‘lower zone’, including controls for an on-screen piano keyboard, a fretboard, a set of drum sampler pads, a piano roll editor, and a mix window. These tools are now all available in play mode, making note input and editing much quicker and offering flexible approaches for keyboard, guitar players, or anyone whose workflow doesn't involve moving notes around a printed score.

For guitarists, Dorico offers the option of retuning the fretboard from standard tuning, and supports an array of pre-programmed instruments, including drop-D, nine-string, 12-string, and banjo variations. The new version also supports capoing the fretboard – giving a chunky visual representation in the editor. Write mode then seamlessly updates any TAB notation to account for the new voicing.

A redesign

Dorico first introduced real-time MIDI recording in version 2.2. If, like me, you remember the horror of having to unpick those early quantised, misspelled attempts at score representations, you'd be forgiven for believing that the latest iteration is something akin to sorcery. The auto-quantise feature makes sense of rhythmic deviations in real-time, allowing the user to view an objective score. The enharmonic spelling is also vastly improved on previous versions. The earth-moving shift, however, has been with Dorico's ability to recognise and represent polyphonic parts sensibly. As a keyboard player, having to edit my playing from a series of reiterated slurred notes into something which approaches standard notation has been an eternal frustration.

So far, Dorico's redesign has focused on the audiation side of the compositional process – the act of getting notes down on a page. The other side of the process is exploration – the process of moving those notes around, analysing, developing and realising those ideas. This is where the newly designed ‘transform’ menu comes into its own. The invert and retrograde functions have long been known to A Level composition students (as anyone who has spent any time marking the results will attest!). Dorico 4 adds a raft of rhythmic transform features and offers the user the opportunity to use these either separate from or in tandem with pitch transform.

Important changes

The other significant feature in the workflow redesign is the ‘jump’ bar. In any complex programme, learning where all the options and functions live is half the battle. Finding the shortcut which works for your workflow is usually the other half! The jump bar acts as something between a spotlight search and a help bar. Hitting ‘J’ brings up a discreet dialogue bar which has two setting: command and go to. The command feature brings up whatever operation you are seeking without having to either memorise a seemingly random keyboard shortcut or navigate a menu.

In most cases, the operation opens a mini-dialogue box, giving you the same functionality as the longhand version. The go to feature allows for precision navigation around your project, either by bar number, rehearsal mark, or flow number. This is probably the biggest workflow changer in the new design, and one which will allow even first-time users to get the most out of the software in minutes – not to mention avoid having to print off pages of shortcut lists for your classroom walls.

The last big redesign to bring to your attention is the new play/mix window interface. For Cubase users, this will look familiar; the play window opens a DAW-style arrange window, with track inspector and routing opening on the left of the screen, and a mix window nestled in at the bottom. Another feature imported from Cubase is the option to open a floating mixer. This also sees the integration of many of the Cubase sound library and editing tools, including SuperVision, a stereo output mastering tool and VST (virtual studio technology) amp racks that allow for realistic re-amped guitar sounds, bass sounds, and the full range of HALion synth tools.

This latest version of Dorico has done much to bring DAW functionality and workflow into the scope of a solid and reliable notation software package. The integration of the two features seems natural to the evolving workflow of the modern composer, which will inevitably include elements of sound design, scoring, and on-the-fly editing. Dorico also supports the use of third party VSTs, allowing the user to integrate external software synths and instrument libraries for a fully customisable sound design. It seems only a short step until Dorico starts supporting audio recording!

Immediate results

The sleek and colourful new Dorico certainly keeps me happy, but I was interested to know how this would work for first-time users. I set a group of my undergraduate students the challenge of scoring a short film, with the provision that the end result would need to incorporate both acoustic and electronic elements. For musicians unfamiliar with producing notation for players, I was keen to see just how fool-proof the new interface is.

Most of the students started work in their own familiar platforms (Ableton or Pro Tools), and imported MIDI tracks into Dorico for editing. We were pleasantly surprised to see that Dorico imported SMPTE offset data, meaning that any notation locked to points in the film were imported with appropriate rest values and starting points, saving several hours of editing time.

The second surprising feature of Dorico's MIDI import was the ease with which the software handled extra controller data – mapping piano pedalling, dynamics and even articulation sets as seamlessly as if we had keyed this data in, rather than playing it into a different platform. The magic of the enharmonic algorithm was already enough. Now I'm feeling positively spoiled!

The Smart MIDI input is another life saver. Files can either be mapped on to existing parts or set on new ones. This sounds like a tiny detail, but for anyone who has moved a large-scale project over from a DAW into a notation package, you will know the horror of spending hours copying and pasting lines so that you don't end up with 20 violin parts, or a second piano which plays two notes in the whole composition. This feature is long overdue, and I tip my hat to the good people at Steinberg for adding it.

The test of time

For the sake of the experiment, we spent a morning in the studio developing the emerging film scores in Dorico to see how the functionality changed our workflow. The ability to either play or draw in input via piano roll proved much faster and more instinctive to our musical team. For the guitarists, the fretboard proved instinctive, but not as fast, and the process of adding chords felt a little clunky for such an obviously chord-based instrument. The acoustic scores and parts flew out at the touch of the jump bar and required very little in the way of editing and formatting to produce easily readable instructions for our team of string and wind players.

Now comes the only frustration with this package. Given the vast and powerful array of sound design and high-level audio mixing and mastering tools available in Dorico 4, it feels counterintuitive that there's no functionality to import the audio captured from our players back into the package to sit with the synthesised parts. Hats off to the Smart MIDI export feature, which made dropping the existing parts into an external DAW the work of seconds, and faithfully preserved controller data. But given that Dorico is so close to being a one-stop-shop for the modern composer, this feature seems the next logical step.

Dorico 4 is priced at £497 (incl. VAT).